Thursday, December 17, 2015

Rene Magritte- The man behind the hat

Magritte in front of his painting ‘The pilgrim,’ photo by Lothar Wolleh, 1967

CONTENTS

Prologue

Lifeline

Part 1

The threatening weather

The lost jockey

The difficult crossing

The invention of life

The discovery of fire

Part 2

The familiar objects

The promised land

Natural graces

The rape

Imp of the perverse

Annunciation

On the threshold of liberty

1st Intermission

The pleasure principle

Part 3

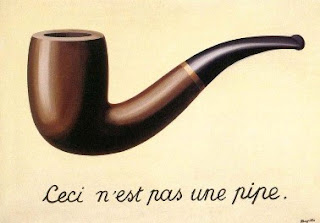

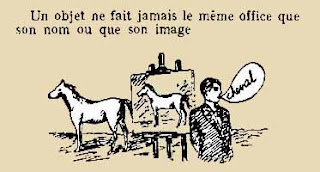

The treachery of images

The key to dreams

The art of conversation

Part 4

Attempting the impossible

The perfect image

The flood

Black magic

The future of statues

Scheherazade

The mask of the lightning

Part 5

The forbidden world

Applied dialectics

Not to be reproduced

The return of the flame

Part 6

The false mirror

The unexpected answer

The beautiful world

The blow to the heart

The human condition

The white race

A little of the bandit’s soul

The seducer

The collective invention

2nd Intermission

The voice of space

The voice of blood

Time transfixed

Part 7

The enchanted realm

The domain of Arnheim

The empire of lights

The son of man

Memories of a journey

Epilogue

Ceci continu de ne pas être une pipe

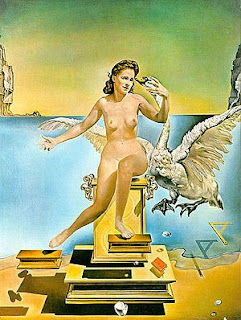

Lifeline

Self- portrait, 1923

“During my childhood, I liked to play with a little girl in an abandoned old cemetery of a country town, where I spent my vacations. We used to lift up the iron gates and go down into the underground passageways. Once, after climbing back up to the light of day, I noticed an artist painting in an avenue of the cemetery, which was very picturesque with its broken columns of stone and its heaped-up leaves. He had come from the capital; his art seemed to me to be magic, and he himself endowed with powers from above.

Youth (Jeunesse), 1924

In 1915 when I began to paint, the memory of that enchanting encounter with the painter turned my steps in a direction having little to do with common sense. A singular fate willed that someone, probably to have fun at my expense, should send me the illustrated catalogue of an exposition of futurist paintings. As a result of that joke I came to know a new way of painting. In a state of intoxication I set about creating busy scenes of stations, festivities or cities in which the little girl bound up in my discovery of the world of painting lived out an exceptional adventure. I cannot doubt that a pure and powerful sentiment, namely eroticism, saved me from slipping to the traditional chase after formal perfection. My interest lies entirely in provoking an emotional shock.

The window, 1925

This painting as search for pleasure was followed next by a curious experience. Thinking it possible to possess the world I loved at my own great pleasure, once I should succeed upon fixing its essence upon canvas, I undertook to find out what it’s plastic equivalents were. The result was a series of highly evocative, but abstract and inert images that were in the final analysis, interesting only to the intelligence of the eye. This experience made it possible for me to view the world of the real in the same abstract manner. Despite the shifting richness of natural detail and shade I grew able to look at a landscape as if though it were but a curtain hanging in front of me. I became skeptical of the dimension and depth of a countryside scene, of the remoteness of the line of the horizon...

Dawn in cayenne (L’aube à cayenne), 1926

In 1925 I made up my mind to break from so passive an attitude. The decision was the outcome of an intolerable interval of contemplation I went through in a working-class Brussels beer hall: I found the door moldings endowed with a mysterious life and I remained a long time in contact with their reality. A feeling bordering upon terror was the point of departure for a will to action upon the real, for a transformation of life itself…

One night museum (Le musée d’une nuit), 1927

I painted pictures in which objects were represented with the appearance they have in reality, in a style objective enough to ensure their upsetting effect- which they would reveal themselves capable of provoking owing to certain means utilized- would be experience in the real world whence the object had been borrowed. This happened by a perfect natural transposition.

The garment of adventure 1926

In my paintings I show objects situated where we never find them. They represented the realization of the real, if unconscious desire, existing in most people. The lizards we usually see on our houses or on our fences, I found more eloquent in a sky habitat. Turned wooden table legs lost the innocent existence ordinarily lent to them, when they appeared to dominate a forest. A woman’s body floating above a city was an opportunity for me to discover some of love's secrets. I found it very instructive to show the Virgin Mary as an undressed lover. The iron bells hanging from the necks of our splendid horses, I painted to sprout like dangerous plants from the edge of a chasm.

The silver gap (Le gouffre argenté), 1926

The creation of new objects, the transformation of known objects, the change of matter of certain other objects, the association of words with images, using ideas suggested by friends, using scenes from half-waking or dream states, were other ways of establishing a connection between consciousness and the real world. The titles of my paintings were chosen in such a way to arouse mistrust in the viewer…

http://www.mattesonart.com/magritte-on-his-paintings--interpreted-and-translated-by-r-matteson.aspx

Elective affinities, 1933

One night in 1936 I awoke in a room where a cage and the bird sleeping in it had been placed. A distortion of vision caused me to see an egg, instead of the bird, in the cage. I had just discovered a new and astonishing poetic secret, for the shock experienced had been provoked by the affinity of two objects (the cage and the egg), whereas before I had provoked this shock by bringing together two unrelated objects. From the moment of that revelation I sought to find out whether other objects might not likewise show the same evident poetry as the cage and the egg had produced by their coming together. In the course of my investigations I came to a conviction that I had always known beforehand that element to be discovered; only this knowledge had always lain as though hidden in the more inaccessible zones of my mind.

The light of coincidence (La lumière des coincidences), 1933

Since this research could yield only one exact tag for each object, my investigations came to be a search for the solution of the problem for which I had three data: the object, the thing attached to it in the shadow of my consciousness, and the light under which that thing would become apparent…

Midnight marriage (Le mariage du minuit), 1926

When, moreover, I found that same will allied to a superior method and doctrine in the works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, and became acquainted about that time with the surrealists, who were then violently demonstrating their loathing for all the bourgeois values, social and ideological, that have kept the world in its present ignorable state, it was then that i became convinced that i must thenceforward live with danger, that life and the world might thereby come up in some measure to the level of thought and the affections…

Study for ‘The infinite chain’ (La chaîne sans fin), 1938

http://www.fine-arts-museum.be/fr/la-collection/rene-magritte-etude-pour-la-chaine-sans-fin?artist=magritte-rene-1

A problem to the solution of which I applied myself over a long period was that of a horse. It was the idea of a horse carrying three figures. Their significance became clear only after a long series of trials and experiments. First I painted a jar and a label bearing the figure of a horse and the letters: ‘Confiture de Cheval’ (Horse Jam). I next thought of a horse whose head was replaced by a hand, with its index finger pointing forward. But I realized that was the equivalent if a unicorn…

The fine idea (La belle idée), 1964

I lingered long over an intriguing combination. What finally put me on the right track was a horseman in the position assumed while riding a galloping horse. From the sleave of the arm thrust forward emerged the head of a noble character, and the other arm, thrown back, held a riding whip. Beside the horseman I placed an American Indian in an identical posture, and I suddenly divined the meaning of the three shapeless figures I had placed on the horse at the beginning of my experiment.

The infinite chain (La chaîne sans fin, 1939)

I knew they were horsemen and I then put the finishing touches to ‘The infinite chain.’ In a setting of desert land and dark sky, a plunging horse is mounted by a modern horseman, a knight of the dying Middle Ages, and a horseman of antiquity.

The prepared bouquet, 1957

Nietzsche was of the opinion that without a burning sexual system Raphael could not have painted such a throng of Madonnas. This is a striking variance with motives usually attributed to that venerated painter: priestly influences, ardent Christianity piety, esthetic ideals, serach for pure beauty, etc. But Nietzsche’s view of the matter makes possible a more sane interpretation of pictorial phenomena, and the violence with which that opinion was expressed is directly proportional to the clarity of the thought underlying it. Only the same mental freedom can make possible a salutary renewal in all the domains of human activity.

Pandora’s box (La boîte de Pandore), 1951

This disorderly world which is our world, swarming with contradictions, still hangs more or less together through explanations, by turns complex and ingenious, but apparently justifying t and excusing those who meanly take advantage of it. Such explanations are based on a certain experience, true. But it is to be remarked that what is invoked is ‘ready-made’ experience, and that if it does give rise to brilliant analysis, such experience is not itself an outcome of an analysis of its own real conditions.

High society (Le beau monde), 1962

Future society will develop an experience which will be the fruit of a profound analysis whose perspectives are being outlined under our very eyes. And it is under the favor of such a rigorous preliminary analysis that pictorial experience such as I understand it may be instituted. That pictorial experience which puts the real world on trial inspired my belief in infinity of possibilities now unknown to life. I am not affirming that their conquest is the only valid end and reason for the existence of man.

http://books.google.gr/books/about/Surrealist_Painters_and_Poets.html?id=-vwXljjkEU0C&redir_esc=y

(From Magritte’s autobiographical text ‘Lifeline’ (Le Ligne de Vie), published in the magazine ‘L’ Invention Collective,’ 1940).

The threatening weather

Threatening weather, 1929

Space is like an empty room. It is defined by the walls and filled by the various objects. Space doesn’t have meaning without its describing limits, its occupying things. On the other hand, things cannot exist without space. Space is the background for objects to appear and support themselves, even if they seem to float.

Even empty space is an object. It is a notion which bares an intrinsic value, and can be represented by many different symbols. A chair, for example, is equivalent to an empty seat. At any time, one sitting on a chair may leave, one leaving behind the vacuum. The empty chairs in our home always remind us of people who left and may never come back. When we leave, the vacuum stays. When we return, disposing emptiness is our major achievement. Our absence has always been more important than our presence.

I would dare say that musical instruments contain harmony. Music then unfolds in the hands of the good musician. A musical instrument is a tool by which the artist discovers new melodies. Our bodies are like musical instruments too. They breathe and vibrate, they make their soul move. And as musical instruments vanish, so do our bodies. They become motionless and empty.

A statue doesn’t need limbs or a head. It is there to express what is implied, just like the half-naked body of a woman. As the vacuum needs its defining limits, so does pleasure need a pocket to be contained in. Within our bodies there is a small capsule filled with pleasure, always ready to break open. In this sense, our bodies are like the torsos of ancient statues, naked and blind, while somebody escapes from within the torso. We then chase our own image, with its multiple expressions, in the real world.

Therefore the vacuum stands both for emptiness and fullness, like the landscape of our loneliness. It is our own presence searching for the missing time and the favorite things gathered in our memories. It was a hole hospitable enough to accommodate life with all its possible arrangements. But someday, when our life ends, we will have to surrender all the precious artifacts back to the vacuum where they belong… It was summertime, by the seaside, as we listened to the storm, approaching the horizon… The sky was clear, the sea was calm, but it is always the growing threat, growing and coming, carrying the sound of silence itself.

Magritte painted the ‘Threatening weather’ in Cadaqués, near Barcelona, staying with Dali, and you see the bay there- Mediterranean landscape. The painting invites us to see the three objects floating in the sky as cloud forms that may turn into a tempest, or something…Magritte never explained his pictures, he always claimed that they did not come from dreams. But they are dream-like in that the relationship between the objects is irrational and inexplicable and it would require Freudian analysis perhaps to make some kind of story out of them; make some sort of sense out of the relationships. But he always leaves it to the spectator to put some kind of story themselves onto the objects that have been put together in this irrational way.

http://www.vidqt.com/id/CN-aHwALB-A?lang=en (VideoID: YT/CN-aHwALB-A)

The tempest, 1931

The tempest, 1932

‘The tempest’ looks as ‘threatening’ as the ‘Threatening weather.’ Instead of the inconsistency of objects, here the threatening element is denoted by the clouds between the ‘skyscrapers.’ The buildings in the first ‘Tempest’ are found inside a room, therefore intensifying the illusion.

The curse (La malédiction), 1931

The curse, 1960

“The sky... Analysis of this considerable object has still not advanced very far. A human history of the sky should be written, to untangle over the course of time this curious labyrinth of impressions, provocations and naive insights, more or less exact physics, slender religious constructions. Here, revelations by painters are rare; and banal if you look through an encyclopedia of painting. Magritte, however, is an exception,” wrote the poet and first owner of ‘The Curse,’ Paul Nougé, in 1947.

From this canvas, full of sky, emanates a discreet absurdity. The world surrounding the sky desperately lacks any system of reference. Although the sky, an ongoing theme in the history of art, has been painted often by many artists, on ceilings for example, and as part of a larger composition, Magritte questions how the sky is represented in seascapes and landscapes. Intrigued, the spectator strives in vain to imagine what there is to be seen in this manifestly empty sky. Here, the painting's meaning lies less its resolution of the enigma, as in the mental exercise it sets the spectator. This mental exercise cannot be an exclusively visual experience, but will also involve the grey matter, our desire to comprehend. From this perspective, isn’t ‘The curse’ a reference to what condemns our gaze to perpetually seek what lies beyond the surface of things?

http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/paintings/rene-magritte-la-malediction-5329707-details.aspx#top

I would say that the 'Curse' represents the shadows of our own thoughts. As the clouds on the sky cast their shadows on a bright day, so our thoughts cast their own shadows on a clear mind. But at the same time the mind cannot exist without thoughts, in the same sense that the clouds define the landscape of the sky. Therefore, there is no reason 'beyond any reasonable doubt.' Doubts are inescapable because they define our own thoughts. Thus the 'Curse.'

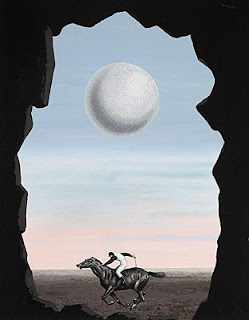

The lost jockey

The lost jockey, 1926

One of Magritte’s favorite themes was ‘The lost jockey.’ In the previous painting, the horse and the rider are stuck in a forest of bilboquet-trees. The horse is galloping, and the jockey leans forward to maintain the speed. Motion takes place in a virtual space, and the spectator seems to be entering a world of new dimensions. The bilboquet-tree on the right is in front of the curtain. Therefore the world of the lost jockey is also part of reality.

Magritte designed theatre sets in Brussels in the early 1920s for ‘Theatre du Groupe Libre.’ The ‘Lost jockey’ is one of many theatre settings with a curtain that Magritte produced in his early works. It also uses bilboquets with musical notation as bark, possibly as a tribute to Mesens, the pianist and composer and his brother Paul, a musician who studied with Mesens. The bilboquet on the right is an impossible object, existing behind and in front of the right curtain.

http://www.renemagritte.org/the-lost-jockey.jsp

The ‘lost jockey’ inaugurated Magritte’s surrealist period, and will appear in more paintings:

The lost jockey, 1942

The lost jockey, 1948

The lost jockey, 1962

The anger of gods, 1960

There is a certain element concerning the impossibility of motion in these paintings. The jockey in ‘The anger of gods’ is on a galloping horse, but at the same time he is not moving in relation to the moving car. The painter challenges the viewer to consider the aspect of motion as an illusion produced in the viewer’s mind through the distortion of dimensions and the interchange between background and foreground.

The hunt in the forest, Paolo Uccello, 1470

According to David Sylvester, a Magritte scholar, this painting by early Renaissance painter Uccello, is the basis for the ‘Lost jockey.’

http://www.mattesonart.com/1926-1930-surrealism-paris-years.aspx

Another of Magritte’s influences was Giorgio de Chirico. Magritte became familiar with de Chirico’s art in about 1925.

Magritte admired de Chirico’s use of dislocation, a combination of incompatible elements of reality, such as a cannon and a clock, within the same picture frame. De Chirico’s smooth, simplified brushwork and pronounced outlines also attracted Magritte who termed this style “the painter’s version of a collage.” Furthermore, Magritte was fascinated by the double illusions de Chirico produced through the depiction of pictures within pictures. These motifs, such as an oil painting within a painted room or an interior space with a window view of another world, interested Magritte because they complicated the relationship between reality and the illusionistic world of art. The close-up frontality of objects in de Chirico's paintings also appealed to Magritte because of its directness and gravity.

http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/citi/resources/Rsrc_001620.pdf

Love song, Giorgio de Chirico, 1914

It is a tribute to the importance of this theme that Magritte himself would write, with reference to his original oil of the subject, that “‘The lost jockey’ is the first canvas I really painted with the feeling I had found my way, if one can use that term.” Magritte’s own revelation had occurred when he had seen a painting by Giorgio de Chirico. Presenting the viewer with an eccentric assortment of seemingly unassociated objects, de Chirico’s ‘Love song’ introduced the viewer to a realm in which another hidden logic appeared dominant. While the mysticism of de Chirico did not influence Magritte, the break with perceived reality and the use of juxtapositions did. For this reason, Magritte denied the open influence of de Chirico, making specific reference to his first version of ‘The lost jockey:’

“If one takes into consideration what I’ve painted since 1926 (‘The lost jockey,’ for example, and what followed), I don’t think one can talk about ‘de Chirico’s influence.’ I was ‘struck’ about 1925 when I saw a picture by Chirico, ‘Love song.’ If there is any influence it’s quite possible there’s no resemblance to Chirico’s pictures in ‘The lost jockey.’ In sum, the influence in question is limited to a great emotion, to a marvelous revelation when for the first time in my life I saw truly poetic painting. With time, I began to renounce researches into pictures in which the manner of painting was uppermost. Now, I know that since 1926 this became clear only sometime after having ‘instinctively’ sought what should be painted.”

http://www.mattesonart.com/le-jockey-perdu-the-lost-jockey.aspx

The blank signature (Le blanc-seing), 1965

In ‘The blanc signature,’ the jockey is lost in the forest. But she is ‘partially’ lost. The front and the rear parts of the horse appear normally inbetween the tree trunks, but the central part of the horse and the jockey are fused. The thin trunk and the vertical stripe of forest on both sides of the jockey create the background- foreground illusion. This is related to the notions of closure and occlusion.

Closure with the horse and woman

Closure is what happens when our brains take a few separate parts of a picture and, because they’re lined up just right, interprets them as a single object. If we black out everything except the horse, it’s easy for closure to do its job and give us a single object.

Occlusion is simply the name for when something overlaps something else. It’s in the perspective toolbox- Object A appears to be in front of Object B if it overlaps it, like so: When Circle A’s outline interrupts Circle B’s, A occludes B.

Our brains constantly use both occlusion and closure to create what we see. Almost always the occlusion and closure information reinforce each other and we get an even stronger impression of space and objects. That impression of what we see, though- it’s not the same thing as what’s really there. It’s just a model. It leaves out all sorts of things and gets other things wrong. Reminding us of this fact was a theme Magritte came back to over and over again.

Background occludes the foreground

A: A tree that should be in the background passes in front of the horse’s leg and body.

B: That same skinny tree appears to occlude the woman’s arm and back. The foliage that comes in around her head means that Magritte can let the larger tree on the right occlude the skinny tree without showing an explicit T intersection.

C: The vertical stripe of background foliage occludes the horse’s body at the shoulder.

Occlusion and closure almost always support each other, but not in this painting. Magritte deliberately sets them against each other to see what will happen. What’s the result? An impossible image that somehow looks right for that split second when we first glance it. By the time our conscious mind is getting around to saying, “Wait a minute…” the perceptual model has already been set up. We’ve already seen a woman on a horse riding through the woods.

http://www.scottmcd.net/artanalysis/?p=115

It is this interplay between the foreground and the background what creates the illusion. But is it an ‘illusion’ or just an aspect of vision? Perhaps this is what happens when we perceive two different things simultaneously. In physics objects have a double reality, both material and wave-like. Each time we have to decide which of the two ‘realities’ we want to measure. Objects are also composed of wave-functions. In ‘The blanc signature’ two different objects, the jockey and the tree-trunks of the forest, are superimposed against each other. Both objects are states of the same system which constitutes the painting. Normally we would choose the state to be expressed by bringing either the jockey or the trees on the foreground. But the painter in this case has somehow managed to paint both states at the same time, while it seems impossible for the viewer to decide which of the two states should be expressed.

The difficult crossing

Cup-and-ball (bilboquet)

During the 1850’s in Europe, bilbo catchers or bilboquets became quite the rage for entertainment. The one shown here is of similar design and the principle is like the ball and cup. On one end of the shaft, the ball is caught in a shallow depression, requiring considerably more practice than in the ball and cup shown above. On the other end of the shaft, the hole in the ball is stuck on the pointed ‘spike’ of the shaft. For those that thing the action cannot be done, we watched an interpreter at a historic site succeeding about 60 percent of the time on the cup end and about one out of three times on the spike end.

http://www.mattesonart.com/biography.aspx

Pleiades, Max Ernst, 1920

Bather between light and darkness, 1935

The balusters- or ‘bilboquets’ as Magritte called them- a kind of piece not unlike the bishop of a chess set, constitute a recurrent prop in the artist’s pictures. Max Ernst called them ‘phallustrades,’ thereby indicating their sexual allusion.

http://www.all-art.org/art_20th_century/magritte1.html

Untitled collage, 1925

Aquis submersus, Max Ernst, 1919

Magritte was inspired by the collages of Max Ernst. According to David Sylvester, Magritte made over two dozen collages from 1925 until he left for Paris in 1927. Note the umbrella pattern (or spider-web) design Magritte began using in some of his early paintings and collages. Here the bilboquet/ pawn has clearly taken on human characteristics. What appears to be an image of Sigmund Freud is pointing the way... but which way?

Nocture, 1925

Master of the revels (Le maitre du plaisir), 1926

Nocturne is one of Magritte’s important early paintings. It established many of Magritte’s icons: the bilboquet, the spider- web design on the floor, and the curtain. It’s also the first painting within a painting. In the ‘Master of the revels’ the picture world is connected, literally, to the real world with a piece of black string. The ‘Master’ walks the tightrope between the painting’s reality and outside world.

http://www.mattesonart.com/early-years--to-1925.aspx

The encounter (La rencontre), 1926

In ‘The encounter’ the bilboquets have taken human form with one eye. Clearly the ‘encounter’ is the group of three bilboquets meeting the other group. Again this is a stage setting with curtains found in many of Magritte’s work.

http://www.mattesonart.com/1926-1930-surrealism-paris-years.aspx

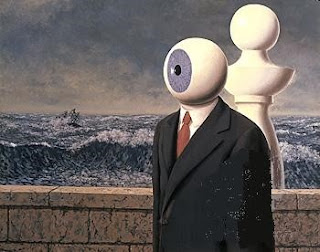

The difficult crossing (La traversée difficile), 1926

Another common feature of Magritte’s works seen here is the ambiguity between windows and paintings. The back of the room shows a boat in a thunderstorm, but the viewer is left to wonder if the depiction is a painting or the view out a window. Magritte elevated the idea to another level in series of works where ‘outdoor’ paintings and windows both appear and even overlap. Note also that the front right leg of the table resembles a human leg and the hand resembles a mannequin hand.

The difficult crossing, 1963

In the 1963 version, a number of elements have changed or disappeared. Instead of taking place in a room, the action has moved outside. There is no table or hand clutching a bird and the scene of the rough sea in the ambiguous window/painting at the rear becomes the entire new background. Near the front a low brick wall is seen with a bilboquet behind and a suited figure with an eyeball for a head in front.

Metaphysical interior with biscuits, Giorgio de Chirico, 1916

The birth of the idol, 1926

Both versions of ‘The difficult crossing’ show a strong similarity to Magritte’s painting ‘The birth of the idol,’ also from 1926. The scene is outside and depicts a rough sea in the background (this time without a ship). Objects which appear include a bilboquet (the non-anthropomorphic variety), a mannequin arm (similar to the hand which clutches the bird) and a wooden board with window-like holes cut out, which is nearly identical to those flanking both sides of the room in earlier version.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Difficult_Crossing

All three paintings may have been inspired by Giorgio de Chirico’s ‘Metaphysical interior,’ which features a room with a number of strange objects and an ambiguous window/painting showing a boat. Magritte was certainly aware of De Chirico’s work and was emotionally moved by his first viewing of a reproduction of ‘Love song.’

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giorgio_de_Chirico

‘The birth of the idol’ may be considered the culmination of the painter’s effort to overpass the ‘difficult crossing’ from purism to a higher level of artistic expression, with the use of surrealistic objects. There is an element of danger is such paintings which is based not on a real threat but on the juxtaposition of unrelated objects and the strange emotions it evokes. The fierce storm, surprisingly though, is counterbalanced by a feeling of security which is produced by the pose of the bilboquet-figurine, standing on another unfinished figurine lying on the table. The latter figurine’s sharp edge points to the rough sea as if it were going to stab the storm. Despite the storm, inside the ‘room’ there is a strange calmness, reflected on the mirror which lies against the wall, as if it formed a protective shield against the wind and the waves. The room again is to be found in the virtual space of our mind, as the room’s windows are lying on the wall, while the stairs are leading nowhere. Also the direction of the idol’s arm opposite to the storm implies the real aspect of an emergency exit. Therefore ‘The birth of the idol’ may represent the figure of the artist’s stance against all odds.

The invention of life

Magritte with his mother, 1899

http://mimisato.blogspot.gr/2011/09/magritte-biography.html

Magritte with his wife Georgette

http://www.surrealists.co.uk/magritte.php

One night in 1912, Magritte's mother Régine Bertinchamp, who suffered from depression, left the house while the rest of the family was asleep and she threw herself over a bridge, into the river Sambre. Magritte (then only 13) was reportedly present when her dead body was retrieved from the water. According to one of the many legends associated with Magritte, the image of his mother floating, her nightgown obscuring her face, influenced a 1927- 1928 series of paintings of people with cloth obscuring their faces.

http://www.mattesonart.com/biography.aspx

The lovers (Les amants), 1928

The incident was described much later by Louis Scutenaire, poet and Magritte’s friend, in words which, according to Georgette, stylized the whole episode into a legend. The only recollection which Magritte himself admitted to having of the affair was that of a feeling of pride at suddenly finding himself the focal point of interest and sympathy both in the neighborhood and among his fellow pupils at the Charleroi grammar school. It is certain that he never saw his mother’s corpse, “its face covered with a nightdress.”

http://www.all-art.org/art_20th_century/magritte1.html

The lovers, 1928

According to Marcel Paquet, “the psychological interpretations of Magritte’s work by David Sylvester and others that the death of Rene’s mother influenced a series of paintings of people with cloth obscuring their faces, including ‘The lovers’ and ‘The heart of the matter’ are unfounded.” This view is supported by the fact in the previous two paintings the hoods are lifted and real faces are revealed (although the body of the man is invisible).

David Sylvester proposes that Magritte might have also copied the idea from a Nick Carter detective magazine (similar to comic book) where the dying heroine mysteriously has her head covered with a sheet. Magritte, a big fan of detective novels, wrote an article about Nick Carter.

The musings of a solitary walker, 1926

The painting that perhaps deals directly with his mother's death is the previous one. Magritte used many iconic images to obscure people and objects. The reason for this had to do little or nothing to do with his mother’s death. He obscured faces with sheets, then birds, pipes and finally apples. Perhaps the real reason for obscuring images besides adding mystery to the person was: the reclusive Magritte was hiding, not wanting to be recognized.

http://www.mattesonart.com/biography.aspx

According to Fred Halper, “From the psychoanalytic perspective, the unconscious wishes, needs, and unresolved psychosexual conflicts of childhood development is the route to understanding Magritte’s creative work. What better candidate for such an approach than the pubescent Rene Magritte insecurely attached to a mother who throws herself in a nearby river, and whose nude body he sees retrieved many days later, with wet nightgown pulled up over her head. The headless body is made visible to him. This, the focus of his Oedipal desire is now uncovered. The occluded is unoccluded, but lifeless…”

David Sylvester, the most prominent historian of Magritte, has called into serious question whether Magritte could have possibly witnessed the retrieval of his mother’s body, as he reportedly told his biographer Louis Scutenaire. Doesn’t this deal a devastating blow to a psychoanalytic understanding of the essential trauma experienced by the thirteen year old Magritte and its influence on his subsequent work? Interpretation is always nourished by flexibility. Psychoanalysis is no different. Perhaps it was the fantasy of witnessing the nude mothers’ body pulled from the river which is all important? The most recent psychoanalytic approach accepts the factual basis of Sylvester’s finding that Magritte couldn’t have witnessed the event and asks us to understand the trauma as typical of all children who suffer the loss of a mother.

Kaplan argues that in such cases ‘screen memories,’ however erroneous, serve to camouflage and transform the more intense pain of the actual life of the mother. In this case, what is screened is the long history of deep depression and attempts at suicide by Regina Magritte. Interestingly, from this point of view, Magritte’s strong identification with Edgar Allen Poe has nothing to do with themes of mystery, poetry or the unknown, but rather their shared trauma of maternal death during childhood.

http://visionlab.harvard.edu/Members/Fred/reprints/pdf's/construal.pdf

One may say that when we have nothing else to do we create problems so that the search for a possible solution keeps as occupied. According to the previous analysis too, “Magritte himself was overtly hostile to Freudian thinking. He resisted the notion of interpretation of his work in general, as well as drawing any specific connections between his psychological development and his art. There was no relationship and psychoanalysis could contribute nothing to the mysteries of life.” Therefore, in some sense, the analysis cancels out itself with the latter statement.

The heart of the matter (L’ histoire centrale), 1928

In ‘The heart of the matter,’ the woman holds the hood she wears by grabbing her throat. Is she trying to strangle herself, or is she just trying not to have her face exposed? Does the face belong to Magritte’s mother, or to another woman? Could it be our own mother, or another person who we have idealized so much that we always try to cover up her common aspects? But the point is that even the painter might have been ignorant of who this person really was. He didn’t originally painted a face, and then painted the hood. Behind the hood there’s no face at all, there's only the empty space of the canvas. Therefore the hood represents a veil of mystery which may be used to add mystery to any implied object the veil covers. It is this effect of implication or of free association the painter uses to give even to the most common objects, like a tuba or a suitcase, special importance.

The invention of life, 1928

The ‘hood’ appears several times in Magritte’s paintings. Magritte once told that he was proud of his mother’s death, as if she had killed herself in an act of ultimate self-sacrifice (for the sake of her own son.) Perhaps this was an illusion but it gave the painter the opportunity to create great art. Not all of us have the same opportunity. It is the condition of creativity Magritte created by making some assumptions and by exploiting the consequences of these assumptions what made the difference. The hood acted like a magician’s veil; each time it was removed, it revealed a new object. By this process of relocation and recollection the painter was also able to redefine the meaning of life.

The symmetrical trick, 1928

In the last paining what seems to be shocking is not the view of the female genitals but the hood the woman wears. The implication of what is missing is far more dangerous than the rest of the object which is visible. What is also interesting is that we are not disturbed by the act of mutilation but by the fact that the mutilated parts don’t match. It seems that the head is found on both sides of the mutilated body. This makes us wonder what a body consists of, and how accurate our perception of reality is. The ‘Symmetrical trick’ therefore concerns the relationship between the real object in physical space and the implied object in the virtual space of perception. The hood is the outline of our mind which covers the event.

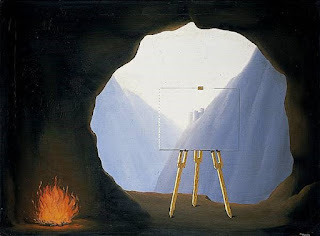

The discovery of fire

The discovery of fire, 1935

There is a certain affiliation between fire and spirit. We may say that fire is a discovery of the spirit, in the sense that one has to be inventive to produce and use fire. One has also to be intelligent enough to manipulate one’s emotions and to evoke the emotions of others. Therefore the spirit is equivalently the product of fire. It is inspired by the burning desires of the soul, like the wind which emerges stronger than ever from the flames.

If we tried to depict this mutual relationship with a single object, this object could take the shape of a musical instrument. The tuba, for example, is well- suited for this purpose because it contains enough free space to be filled with air. The fire in this case would come from the air inside the guts of the musician, it would be transmuted by the curvature of the instrument, and it would be expressed in the form of music. Then the tuba would be an object uniting the two basic elements, fire and air, in harmony.

The ladder of fire I (L’échelle du feu), 1934

In fact air and fire are both aspects of harmony. Fire ascends toward the spirit, while the spirit understands the process by descending in the soul. According to the Unruh effect in physics, an observer accelerating in the vacuum will perceive a heat bath of radiation hitting him. We may say that whatever moves feels the effects of his own background in the form of friction. At the same time the energy of the background is expressed as a certain function of the moving object. If the object is a particle, it is expressed as vibration. If it is a shooting star it is expressed as a comet’s tail. If it is a burning soul it is expressed in the form of wishes. In the case of running thoughts it is expressed in the form of ideas. All ideas correspond to objects. Ideas are objects with burning form.

Magritte compared this painting to the caveman’s first discovery of fire. He said in a 1938 lecture, “‘The ladder of fire’ afforded me the privilege of being acquainted with the feeling experienced by the first men who produced a flame by rubbing together two pieces of stone.” He follows this up with his 1936 ‘The discovery of fire.’ The discovery is more apparent here; the paper can burn, the chair can burn, but the tuba cannot burn- making the burning tuba an impossible object. This impossibility is what Magritte is trying to convey.

http://www.mattesonart.com/1931-1942-brussels--pre-war-years.aspx

The familiar objects

View from the window at Le Gras, Nicéphore Niépce, 1826- 1827

This is the oldest surviving camera photograph, and was created by Nicephore Niepce, in 1826 or 1827, at Saint-Loup-de-Varennes. It shows parts of the buildings and surrounding countryside of his estate, Le Gras, seen from a high window. Niepce captured the scene with a camera obscura focused onto a pewter (mainly tin) plate coated with bitumen of Judea (asphalt). The bitumen hardened in the brightly lit areas, but in the dimly lit areas it remained soluble and could be washed away with a mixture of oil of lavender and white petroleum. A very long exposure in the camera was required. Sunlight strikes the buildings on opposite sides, suggesting an exposure that lasted several hours, or even days.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/View_from_the_Window_at_Le_Gras

19th century studio camera standing on tripod and using plates

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photography

The Therapist (Le Thérapeute), 1937

The Therapist, 1962

Before the discovery of photography, painters used to make a living by drawing portraits among other things. Portraits and landscapes were a common feature for a painter during the Renaissance. But as soon as photography was invented it seemed painters were threatened to lose their jobs. After all, a photograph was able to depict a face, object or landscape much more accurately than a painting. Therefore accuracy lost meaning for a painter, while abstraction began. So painters started to imagine things that didn’t exist in the real world. Things that even an abstract photographer could not capture. This way, painting could still find a place in modern art, besides photography.

The secret player, 1927

At the same time painters and artists in general began wondering if the unreal (or surreal) objects they tried to capture could be common objects referring to a ‘collective soul.’ For example, are the objects used by Magritte in his paintings recognizable by everyone? Can in ‘The secret player’ anyone participate in this ‘secret game?’ Everyone is familiar with the pieces of chess or the balusters of staircases. The symbol is the same, recognizable by everyone, only the interpretation changes. In fact, Magritte’s bilboquet is a fundamental structural element in his paintings. In the form of trees, bilboquets built a forest, and the bat of the cricket player is made of the same material (wood). As the curtain rises, we found ourselves in the world of dreams. The creature hovering among the ‘trees’ looks strangely familiar. It looks like a water bottle transformed into a headless creature. The gray lines on its black back emphasize its ability to float or fly, while the woman on the right has her mouth covered. The mysterious secrecy of the painting points directly to a dream state, while the position of the cricket players (the fieldsman comes before the batsman) seems to defy causality.

The familiar objects, 1928

The surrealist objects, since they are not found in reality, may gravitate with each other in a non- physical way. In the previous painting, some of the painter’s ‘familiar objects’ float in front of the spectators’ eyes. I have the impression that there are not many spectators but just one, captured in different time frames, watching, or better imagining, the same ‘super-object,’ or ‘sur-objet’ in its different manifestations. It’s hard to imagine the common characteristic which could unite all these separate objects into a single ‘super-object.’ One such characteristic could refer to a common property of these objects. An alternative explanation is some memory of the painter. For example, drinking wine (the jar), by the sea (the sponge and the shell), with a woman (the headdress), bitter as lemon. This is a common memory, referring to anyone of us. However, neither the sequence nor the combination of these events is unique. For example, what combines them could be the element of ‘blue.’ The headdress is blue, the sponge and the shell refer to water, while the lemon as well as the jar may contain water. In any case, the simplest common property which unites both the objects and the persons in the painting is the mind of the painter, and the defiance of gravity in a mode of meditation. Therefore, these phenomenally incongruous objects may coincide at a deeper level in a meaningful way.

Personal values, 1952

I have found an interesting analysis about this painting, which, by the way, is one of my favorites: “In ‘Personal values,’ Magritte shows a bedroom filled with everyday objects that are juxtaposed together in blown up proportions. These everyday objects include a comb, a matchstick, a wineglass, a bar of soap and a shaving brush. They seem to be scattered around the room with no apparent order. Their presence in the room and the scale in which they are depicted suggests to the viewer that the room is fully decorated. The wallpaper of the room’s walls displays white fluffy clouds and the azure blue sky. From the reflection on the mirror, a single window can be seen with white curtains draped at the side.”

Mirrors, curtains, the sky and the clouds are some of Magritte’s favorite items. The relative proportions of some of the other objects, however, are indicative of the painter’s personality. For example, the bed is proportionally the smallest, suggesting that the painter doesn’t like to sleep much. He could equally spend his time sitting on his poof-chair, which is as big as the bed. The huge comb and shaving brush denote a narcissistic personality, enjoying wine in the enormous glass, while the big matchstick on the carpet reminds of some equivalence between the shape of trees and lit matches.

What also makes the painting interesting is its impossible elements. The cupboard, for example, is a ‘double mirror,’ since it reflects the poof-seating, but also contains part of the sky, as well as the window, whose curtain imitates one of the cupboard’s legs. Therefore, the mirror of the cupboard is a ‘window’ itself, both showing the exterior and reflecting the interior.

The same analysis goes on: “The strong and rich colors found in the painting add a touch of exuberance and joy to the painting. The overall mood of the painting is also rather calming and serene, especially with the clouds painted on the walls of the room. A sense of harmony is also created with the miraculous sense of balance achieved by Magritte despite the varying textures, colors, shapes and sizes in which these objects are portrayed.

Despite the uplifting mood created, a sense of confusion or puzzlement is brought about due to the unusual proportions of the objects. The varying scales of each object draw the attention of the viewer as he takes in the whole painting. The unrealistic size of these objects holds the surrealistic quality of the painting…

In my opinion, the objects portrayed in this brilliant artwork are likely to belong to the artist himself. This conclusion is made based on Magritte’s writing, saying, “Painting for me is a description of a thought. The thought can only consist of visible objects, which exist in my head as clear imaged. A comb for example, I make a lot of drawings of it. That in turn will suggest other images- a wineglass, a shaving brush…” Magritte may have included these objects in this work with the objective to cause viewers to think about their own personal values and more importantly, rethink their significance in their lives. This is where the blown-up proportions of these objects come into play as Magritte tries to highlight the importance of these objects. The viewers are then stimulated to rethink about their relationship with their ordinary personal items, to question their thoughtless, hasty and routine interactions with familiar objects that usually cause these objects to be belittled and ignored. As such, viewers will stop and assess their values and importance, thus the title of the work, ‘Personal values.’”

http://thoughtwithoutabox.wordpress.com/2012/08/26/rene-magritte-les-valuers-personnelles-personal-values-1952/

What I like most about ‘Personal values’ is that it explicitly illuminates the painter’s everyday life: A small room to paint, some basic commodities (a bed, a cupboard and a poof-chair, a comb and a shaving brush, etc., and a lot of fantasy of course!

The promised land

The promised land (La terre promise), 1947

As well as bilboquets, Magritte used ‘cicerones’ or ‘cicerines’ in his paintings. The only human thing in ‘The promised land’ is the hands of the cicerines. One of them is holding two leaves, while the other one holds a glass with one hand, while with the other hand it holds the former cicerine. The glass is empty but it looks red because of the reflection of the cicerine’s red garment. The heads of the two cicerines touch one another, suggesting a close relationship, sexual or kinship. Oddly enough the second cicerine seems to appear from within the mirror as a reflection of the other cicerine, although parts of it are not inside the mirror. It is a sort of double reflection, half of which belongs to the real world and the other half to our own perception. The three bells or spheres suggest a triadic element perhaps related to the religious aspect of the title, but perhaps they are less than three- the third sphere at the back is most likely a reflection. In any case, the ‘three’ spheres offer a very vivid representation of a fixed idea- that of the ‘promised land,’ which the painter deserved and gained, a place found in a small room decorated with some of the painter’s familiar objects.

Cicero, 1947

Cicero, 1965

Cicero is one of the prominent philosophers of antiquity. According to Michael Grant, “the influence of Cicero upon the history of European literature and ideas greatly exceeds that of any other prose writer in any language.” A characteristic of his is the neologisms he brought into Latin, and in turn into English, such as the words humanity (humanitas), quality (qualitas), quantity (quantitas), and essence (essential).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cicero

Therefore, Magritte had two reasons, among others, to admire Cicero. Firstly Cicero was an excellent philosopher, and secondly he was also the creator of new objects (words in this case). Magritte in his paintings presents Cicero as a person possessing the ‘fire of speech,’ coming out of his mouth, in the daytime, while at night he stands by the window, under the moon, contemplating. In his hands he holds the ‘leaf of piece’ or the ‘triple candlestick’ (perhaps corresponding to Cicero’s full name, Marcus Tullius Cicero, which incidentally was the same as his father’s).

The rights of man, 1947

Elementary cosmogony, 1949

Therefore, the identification of Magritte’s fire with a spiritual symbolism is confirmed. It may also be suggested a correspondence between the male-oriented cicerine and the female-oriented trumpet, as representations of a father-mother pair. In ‘The rights of man’ Cicero offers ‘earth and water,’ corresponding to the leaf and the glass, to cover the basic needs of humanity, while the burning trumpet represents the other two elements- air and fire. In ‘Elementary cosmogony,’ the philosopher rests on the ground, with his sphere of contemplation by his left hand.

Natural graces

Plain of air, 1940

Leaf customs, Max Ernst, 1925

The leaf motif was not unique to Magritte as we see. Max Ernst painted leaves having the water marks of wood, making thus wood a fundamental structural element in art. In the ‘Plain of air,’ Magritte in turn transformed the leaf to the tree itself, suggesting a fundamental unity in nature, together with the ground and the sky.

Project of poster ‘The center of textile workers in Belgium,’ 1938

At the first clear word, Max Ernst, 1923

Magritte cannot be considered a major (political) activist, but when he was engaged in painting posters for trade unions, he left surrealism aside. The spindle however is a common surrealistic object. In Ernst’s painting for example, the symbolism of the spindle overlaps with the symbolism of a cup-and-ball (bilboquet), which is held by the hand in a very characteristic way. The sadomasochistic atmosphere of the painting, accompanied by the insect at the top left, and toned by the contrast of red and green colors, belongs to Ernst’s surrealistic landscape. But the match-stick trees resemble representations in Magritte’s paintings.

The good season (La belle saison), 1961

Clairvoyance (La clairvoyance), 1962

Leaf-like trees (or tree-like leaves) in Magritte paintings are in fact an ‘ultra-surrealistic’ representation of nature, a detailed and consistent reductionism with which we recognize the whole in the parts, but also a unique harmony between the parts. In the second painting, Magritte’s tree is compared to a ‘real’ tree. It is remarkable to note that Magritte's ‘leaf- trees’ are unique, in the sense that they could be real trees, under different evolutionary processes. This is why Magritte used to say that his paintings were not ‘fantastic,’ but instead representations of real things, though depicted in an exaggerated and uncommon way.

Companions of fear, 1942

The taste of tears, 1946

Island of treasures, 1942

The natural graces, 1963

This is a group of paintings where leaf-like representations are transformed into birds. If trees could fly (or if birds had roots), their leaves may have looked like Magritte’s depictions. In the ‘Companions of fear,’ the owls grow right from the bush beneath, like the plumage which grows from our minds when we dream. The owl could be seen as a scary creature, hovering just above us as we walk in a forest at night, but also, as a bird of wisdom, which comes as a companion to guide us throw our most thick and dark fears. In ‘The taste of tears,’ the caterpillar has climbed from the plant to the bird, leaving its marks on its chest, on which we see the veins of a leaf. This is a very successful opposition between roughness (the caterpillar) and tenderness (the leaf), while the bird bends its head in a passive expression.

‘The treasure island’ is a novel of Louis Stevenson, first published as a book on 23 May 1883, and perhaps Magritte had read it or knew the title. Anyway, while the original story was about pirates and the lost treasure, Magritte’s ‘Island of treasures’ is about a barren island with just a nest of birds, which are growing from the ground like leaves.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treasure_Island

Therefore Magritte’s ‘lost treasure’ is not to be found in gold but in the luxury of being able to enjoy the atmosphere of tranquil eternity on a remote island. The ‘Natural graces’ epitomize this message of pure naturalism expressed by the entangled features of surrealism.

The giantess (La géante), 1929-1930

The first ‘Giantess’ of Magritte features a miniature man entering a room with a seemingly huge nude woman towering above him. The scales of the painting are characteristic: While the closets and the table have the right dimensions with respect to the lady, the door and the couch are too small, even for the ‘little man’ who seems to be approaching the room. Also, the painting on the wall looks proportionally huge.

The giantess, 1935

The giantess, 1936

In a letter to Andre Breton in 1934, Magritte discussed the seeds of the idea that led to the creation of the ‘Giantess,’ saying that he was trying to discover what it is in a tree that belongs to it specifically but which would run counter to our concept of a tree. This was a part of Magritte’s pioneering adventures into the nature of the world and our perceptions, disrupting the absolute expectations people have about the nature of specific objects. So with the tree, Magritte sought the idiosyncratic, signature element that he could disrupt in order to confront the viewer with a new, fresh view of the tree. He did this by twisting the associated elements of the object, forcing the viewer's reappraisal of the commonplace. This solution was disarmingly simple: The tree, as the subject of a problem, became a large leaf the stem of which was a trunk directly planted in the ground. The name for these leaf-like representations comes from a poem by Baudelaire. In the poem, which is mentioned by Magritte, Baudelaire imagines himself exploring and roaming over the body of a giantess. The first verse of the poem goes like this:

“Du temps que la Nature en sa verve puissante

Concevait chaque jour des enfants monstrueux,

J'eusse aimé vivre auprès d'une jeune géante,

Comme aux pieds d'une reine un chat voluptueux.”

“At times when Nature expressed herself so eloquently

Conceiving monstrous children every day,

I’d have liked to live beside a young giantess,

At her royal feet like a voluptuous cat.”

http://www.mattesonart.com/1931-1942-brussels--pre-war-years.aspx

Search for the absolute, 1940

Gigantic figures standing, in comparison, against miniscule ones, serve two purposes; firstly, to expose a game of perspective, of an interplay between the figure and the background; secondly, and at the same time, to denote the symbolism of the larger figure with respect to the smaller one. In the previous painting, the gigantic tree and the huge ball stand imposing one beside the other, in contrast to the two small human figures. The fact that the human figures are two suggests a dialogue. The painter here is not alone but with somebody, having together a conversation, perhaps wondering about the miracles of life. Their relative miniscule size compared to that of the tree and the ball give a sense of humility against the mysteries of nature and of the human spirit. Therefore the final cause of the high standing leaf-like trees and leaf- like representations is the ‘Search of the absolute,’ is a symbolic representation of the ‘tree of life,’ which synopsizes in its network of veins the history of mankind, and of the ‘ball of wisdom,’ which contains all knowledge.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Introduction_to_quantum_mechanics

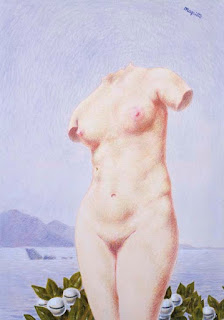

The rape

Courtesan’s palace, 1929

The disguised symbol, 1928

The same reductionism or abstraction Magritte used in leaf-life representations (where the leaf looks like the tree, and vice-versa), is found in ‘body-faces.’ Here, the characteristics of the middle part of the human body are painted in a way to imitate the expressions of the human face. The nipples look like the eyes, and the bellybutton together with the shadowy fold above it resemble the mouth and a chin dimple. The dark areas of the paintings help this ‘body language’ stand out.

The eternal evidence, 1930

In ‘The eternal evidence,’ a headless body of a woman appears split into sepate frames, as if in a photographic film, while the parts are recombined in such a way to form the whole picture.

The eternally obvious (L’évidence éternelle), 1930

The eternally obvious, 1948

Magritte holding ‘The eternally obvious,’ Paris, 1930, The Menil Collection

http://www.steeliman.com/2013/11/matin-avec-magritte.html

In ‘The eternally obvious’ (1939), the whole picture emerges, though again in separate parts, of Georgette, Magritte’s wife and model. In 1948, Magritte replaced Georgette with some other model.

A famous man, 1926

Representation (La représentation), 1937

The same analysis of the whole into parts, which nevertheless may stand on their own, forming totalities themselves, occurs in the ‘Famous man,’ with a bilboquet. Its missing head reappears on the top left of the painting, hanging upside-down. In ‘Representation,’ a woman’s vagina is painted in such a way that it seems to be smiling.

The rape (Le viol), 1934

The rape, 1935

The culmination of Magritte’s effort to unify the language of the human body with facial expression is ‘The rape.’ Here, the body with facial characteristics reverses into a face with body-like characteristics. Again the eyes are the same as the female nipples, the naval stands for the nose, while the mouth takes the place of a vagina. The hair on the ‘head’ are certainly suggestive of pubic hair.

The rape, 1948

In the last ‘Rape,’ the violation of our understanding of the human form is completed, as the face and the rest of the body of a woman have totally merged together. The legs appear as the jaws of an alien creature just below its implied mouth, while the growth of the hair covers the body all the way down. The whole form of the body in the painting stands exactly for the head which is missing.

In Magritte’s own words, in ‘The rape’ a woman’s face is made up of the essential features of her body. So composed, the face reflects the secret desires of the painter and the observer that some women can convey their sexuality in the way in which they look at one. Painting, the art of rendering things visible, reveals its ability here to record impressively the constant sex-appeal which leaves its mark upon almost every moment of our lives. The selection of the work’s title indicates the ongoing conflict of the voyeuristic observer; Magritte comes very close here to Hans Bellmer’s erotic perversion, albeit without the latter’s sadness. He has destroyed what is most obvious of all, namely the face, replacing it with something even more obvious. It is the shock effect of the picture together with the basic idea lying behind it, which represent the key components of his work.

http://www.all-art.org/art_20th_century/magritte1.html

The act of violence (L’attentat), 1932

It has been suggested that ‘The rape’ series of paintings are the painter’s protest against the war. However, such paintings find their roots back in collage techniques and the quest of the painter to cut reality to pieces and recompose it in a unique and indicative way. Magritte was opposed to reality as we normally conceive it. Neither was he a hedonist, although some translated the ‘Rape’ as such. In ‘The act of violence,’ we see again that the ‘violence’ taking place is metaphorical; it’s a violation of common imagery.

Imp of the perverse

The female thief, 1927

The discovery, 1927

When I first saw ‘The discovery,’ I thought it was a depiction of a ‘leopard-lady.’ However, as the pose of the woman seems to be following the stripes on her body, a better explanation is that the figure is created by the ‘curvature of the canvas.’ The painter’s paint itself has this property of fluidity, as if the only thing a painter had to do was to follow the paint while flowing.

Imp of the perverse, 1927

In this painting, the ‘principle of fluidity’ can be better examined in the water marks on a piece of wood. The marks remind us that the wood used to be alive, so that the marks contain all the history of the corresponding tree, its environment, the rain it absorbed, the ground it used to stand on. Therefore, wood serves both as a construction material and as a functional object. It supports the painter’s canvas, but also tells the story of its past life to one’s trained eyes and ears.

The ‘Imp of the perverse’ is a metaphor for the common tendency, particularly among children and miscreants, to do exactly the wrong thing in a given situation. The conceit is that the misbehavior is due to an imp (a small demon) leading an otherwise decent person into mischief. The phrase has a long history in literature, and was popularized (and perhaps coined) by Edgar Allan Poe in his short story, ‘The imp of the perverse.’ It is also exemplified in ‘The bad glazier,’ a prose poem by Charles Baudelaire.

http://www.polishforums.com/off-topic-47/imp-perverse-46151/

The conqueror (Le conquérant), 1926

The man of the sea, 1927

‘The conqueror’ depicts a musician dressed in formal attire, sporting by a black bow tie. A wooden plank replaces the head with two plant like, violin like, decorations. It reminds of a tenor about to sing an aria. This is a common Magritte use of musical notes in a collage probably used as a tribute to his brother Paul and close friend E.L.T. Mesens, both musicians.

http://www.mattesonart.com/1926-1930-surrealism-paris-years.aspx

In the second painting, we realize that the ‘man of the sea,’ as well as ‘the female thief’ we saw before, are depictions of the same persona- the ‘anima’ and ‘animus’ of the same person. The uniform the figures wear is very descriptive of the asexual (or bisexual) representation of a painter’s doll. This is very helpful however, because it lets us concentrate on some other, otherwise invisible, characteristics of the human body. First of all, we may discern its similarity (in fact its origins) with a tree. We all come from the forest, not only as primitive dwellers, but also because we recognize a part of our own in the story it tells. The whispers of a forest may sometimes be printed on the wood, like musical annotations, so that the tree trunk may take half the shape of a tree and half of a violin. The water marks now become imprints of the spectrum of the sounds in the forest of our soul.

Magritte’s ‘The man of the sea’ is strongly reminiscent of the ‘Sandman.’ It is a short story written by E. T. A. Hoffmann, in 1817. The story revolves around a ‘doll’ (automaton) called Olympia. One of the protagonists (Nathanael) falls in love with Olympia. He begins to watch Olympia from his window through his telescope, although her fixed gaze and motionless stance disconcert him. Spalanzani (Olympia’s ‘father’) gives a grand party at which it is reported that his daughter will be presented in public for the first time. Nathanael is invited, and becomes enraptured by Olympia who plays the harpsichord, sings and dances. Her stiffness of movement and coldness of touch appear strange to many of the company. Nathanael dances with her repeatedly, awed by her perfect rhythm, and eventually tells her of his passion for her, to which Olympia, repeatedly, replies only “Ah, ah!”

Eventually Nathanael determines to propose to Olympia, but when he arrives at her rooms he finds an argument in progress between Spalanzani and Coppola (an Italian trader), who are fighting over the body of Olympia and arguing over who made the eyes and who made the clockwork. Coppola, who is now revealed as Coppelius in truth (a frightening, large and malformed man), wins the struggle, and makes off with the lifeless and eyeless body. The sight of Olympia’s eyes lying on the ground drives Nathanael to madness, and he flies at the professor to strangle him. He is pulled away by other people drawn by the noise of the struggle, and in a state of insanity is taken to an asylum.

A modern version of the Sandman

http://whatculture.com/film/50-greatest-marvel-movie-moments.php

Nathanael recalls his childhood terror of the legendary Sandman, who is traditionally said to throw sand in the eyes of children to help them fall asleep. Nathanael struggles his whole life against posttraumatic stress which comes from a traumatic episode with the sandman in his childhood experience. Until the end of Hofmann’s book it remains open whether this experience was real, or just a dream of the young Nathanael.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sandman_(short_story)

Landscape, 1926

The wreckage of the shadow, 1926

The similarity between the ‘Sandman’ and the ‘Man of the sea’ is apparent. The merge between human characteristics and inanimate matter (or plants and animals) was further explored by Magritte in his paintings.

In ‘Landscape’ there is another representation where the branches of a tree have merged with the veins of a human body. The head is formed by arm-like extensions; therefore it is more a body-like tree, rather than a tree-like body. This priority is also depicted in the rocks behind, which seem to be wearing vests.

In ‘The wreckage of the shadow’ there is a high degree of symmetry, combining objects and notions. The upper part wooden frames resemble the eagle’s head mountain at the left top, while the mountain on the right reappears within its own cave, at the bottom. The eagle seems to have left some of its feathers on the panel with the strange grid, which balances on one vertex at the center of the painting, while, just below, the feathered head of an eagle, standing on a stick and pointing at the opposite direction, completes the symmetries of the composition.

The comic spirit (L’ esprit comique), 1927

The finery of the storm (La parure de l’ orage), 1927

In the previous paintings, meaning has given its place to a more scholastic kind of painting. Ornamental vertical cutouts placed in front of a desolate seascape appear to be collaged on to the canvas- so dense, hard-edged and object-like are they. In fact, these ornamental totem poles are painted on to the canvas, producing a striking juxtaposition of an illusionist background and relief-like, tangible foreground. In fact, Magritte’s father was a taylor, so young Magritte may have many time watched his father to cut and tie pieces of cloth together, transfering later on his father art on the canvas.

http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/magrittes-lonely-art

The end of contemplation (La fin des contemplations), 1927

The same technique is employed in ‘The end of contemplation.’ The faces, as well as the shape behind them, seem to be cut out of paper edges, which form the nose, the mouth, the chin, as well as parts of the body. I would say that by merging or deleting the facial expressions, the painter forces us to accept a unified sense of reality, consisting of the experience of all senses simultaneously, making us reach this way the limits of contemplation, where common experience and artistic creativity come together.

Annunciation

Annunciation, 1930

The double secret, 1927

The iron-like balls (or bells), attached to strings (or just floating) in Magritte’s paintings, remind me of space machines, coming to our world to inspect us, with eyes hidden behind the gap all around the perimeter of these spheres, which could be something like flying saucers. But, despite what most people think, these objects come (at least most of the times) not from outer space but from within our unconscious mind. This is why all these ‘UFO’s’ seem so familiar to us.

‘Annunciation’ means ‘the announcement of divine incarnation.’ Therefore, in this painting, whether its implications are religious or not, we have the materialization of Magritte’s familiar surrealistic objects, such as the bilboquets, collage paper, together with an iron curtain full of iron balls or bells. The iron curtain certainly implies segregation, either religious or political. Someone could say that with this painting the painter wants to split parts with the rest of the surrealists or with the church or, on the contrary, that he wants to protest against the division between the ‘surrealistic’ and the ‘divine.’

Magritte certainly was not a strong believer in religion, and he probably considered the mystery of ‘annunciation’ in a secular sense. From the surrealistic point of view of course, the title could only be ironic. Magritte had quarreled with the leader of the French surrealists, André Breton, on a matter relating to religion in December 1929, and the rift between the two men was to last until 1933. At a gathering at his home, Breton, who, like all the surrealist writers, was an arch-atheist and anti-cleric, noticed that Georgette was wearing a cross, and asked her to take off ‘that object’. Georgette habitually wore the cross, which had belonged to her grandmother, and preferred to leave with her husband rather than remove it. Magritte was deeply angered and upset by this seemingly rather trivial incident, and rejected attempts by friends to effect reconciliation. Yet the fault was not all on one side: many present at the incident felt that Magritte’s hostile response was not entirely justified, particularly as it seems that he had long attempted to provoke Breton on the subject of religion. Patrick Waldberg writes, “At the meetings Magritte had for some time been making a custom of harrying Breton with ‘embarrassing’ questions bearing upon religion- “Tell me, Breton, what do you think of Jesus Christ? What is the view you take of the Virgin Mother? Breton, have you pondered the Catholic mystery?”

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/magritte-the-annunciation-t04367/text-catalogue-entry

However, the message has to go much deeper than this. The iron curtain certainly implies a division, which is exaggerated by the other surrealistic objects, such as the cutout paper and the bilboquets against a natural landscape with trees, rocks and the sky. But this division is between the painter and the rest of the world. On the one hand, there is the surrealistic expression and understanding of things, while, on the other hand, there is the common interpretation of everyday objects. But the iron curtain itself with its strange hanging balls forms itself a strange wall, a metaphysical limit which everyone would like to pass to see what’s happening on the other side. Also, the one-to-one correspondence between the sky and the ‘curtain,’ the trees and the bilboquets, the rocks and the cutout paper, suggests that this interpretation is correct. The painter wants us to see the other side of familiar objects, and help us pass to a parallel, transcendental world.

The same sort of comparison is proposed by the two faces in ‘The double secret.’ One face is ‘normal’ but its missing parts are suggestive of its susceptibility to transformation. This transformation takes place with the second face, inside which we find the strange strings with bells. The first face is standing at the back, and its missing parts are parts of the sky or of the ocean, while the second face stands forward with no parts missing, except his interior organs which are substituted by the string of bells. Therefore, the painter brings forward the secret of this double reality, the inside world against the outside world, giving the impression of two faces, whereas there is presumably only one.

On the threshold of liberty

The palace of curtains (1928-1929)

In ‘The palace of curtains’ we see two mirrors, or two paintings of mirrors, lying against the wall. The ‘mirrors’ themselves can been seen as reflections of real objects and notions of objects (the sky and the ‘blue’ (ciel) respectively), or as entrances into what lies behind them. But paintings, as well as mirrors, are two-dimensional objects. In this two dimensional perspective, Magritte compares objects and notions concerning these objects. The notion of ‘blue’ is one of the basic elements of Magritte’s cosmogony, related to the notion of the sky.

The empty mask, 1928

The fixed idea (L’ idée fixe), 1927

The six elements, 1928

In ‘The empty mask,’ Magritte reveals more of his basic elements. Four words correspond to six images. The ‘blue’ on the left corresponds to the sky with clouds on the right, the face of a house (façade de maison) corresponds to the same image on the right, the human body corresponds to the forest, while what remains is representations of the notion of a curtain (rideau). Therefore the prevalent characteristic of the painter is his tendency to hide clues behind curtains.

There is some uncertainty about Magritte’s titles, but it is worth comment that both assemblies are called ‘empty,’ perhaps for different reasons. That is, it is easy to see the absence of images in the first version as the emptiness of the frames, but in the second, the mask is still empty because all masks are empty, at least those that do not represent anything, that are merely a decorated screen. Here Magritte may be playing off of the ‘frame’ convention: these segments can’t represent because they are not presented in proper rectangular frames. The title evokes the fear of the invisible which pervades the artist's work and reflects the surrealists' fascination with the subconscious.

http://courses.washington.edu/hypertxt/cgi-bin/book/wordsinimages/magritte.html

Again, there is a perfect correspondence between the words in ‘The empty mask’ and the images in ‘The fixed idea,’ except one- the ‘curtain’ of course. I guess this is not coincidental, either it was intentional or not. What is also strange in ‘The fixed idea,’ is the identification of the ‘human body’ with a ‘hunter,’ probably Magritte’s friend Luis Scutenaire. At least this is what one might first think, because if either the ‘forest’ or the ‘human body’ are represented by the forest, then the hunter can only be identified with the ‘curtain.’

The ‘Six elements’ therefore combine the basic elements of Magritte’s cosmogony. If we compare this paining to the images in the ‘Empty mask,’ we find that the ‘body- face’ is identified with the cutout paper. While all images in Magritte’s paintings can be representations of other images hiding behind mirrors or curtains, the constant element is that of ‘blue.’ I would say that ‘blueness’ is the painter’s last stop before absolute emptiness (or fullness).

The conquest of the philosopher, Giorgio de Chirico, 1914

On the threshold of liberty, 1930

It is perhaps interesting to compare this notion of ‘blueness’ with the notion of the vacuum in modern physics. In contrast to what was previously believed, the quantum vacuum is not empty, but it is full of elementary and subtle motions of particles, or ‘entities,’ which finally form everything we know. We consider particles as ‘very small round objects,’ but they can be of any shape, or of no shape at all. In fact quarks are identified with ‘flavors’ (up, down, strange, charm, bottom, and top), and their charges with the three basic colors (red, green, and blue).

Wikipedia warns us that, the ‘color charge’ of quarks is completely unrelated to visual perception of color.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_charge