[http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/61/C%2BB-Geography-Map1-StrabosMap.PNG]

Contents

1. Prologue

1.1 About Strabo’s geography

1.2 Purpose of this survey

1.3 The scenery

1.4 The world of the Pelasgians

2. Stabo’s toponyms by place

2.1 Iberia

2.2 Keltiberia

2.3 Keltica

2.4 The Alps

2.5 Britain

2.6 Italy

2.7 Rest of Europe

2.8 Greece

2.9 Asia

2.10 Rest of Asia

2.11 Africa

3. Taxonomy of toponyms

3.1 First Taxonomy

3.1.1 Endings in –os

3.1.2 Endings in –s

3.1.3 Toponyms in –ssa or –si

3.1.4 Toponyms in –ra

3.1.5 Toponyms in –mna

3.1.6 Rest of endings

3.1.7 Examples of ambiguity

3.2 Second taxonomy

3.2.1 Toponyms in –sos and –si

3.2.2 Toponyms in –nth

3.2.3 Toponyms in –ra

3.2.4 Toponyms in –na

3.2.5 Toponyms in –quos

3.2.6 Rest of themes

4. Analysis

4.1 Replacement vs. Continuity

4.2 Successive suffixation

4.3 Transformations

4.3.1 Reversals

4.3.2 Omissions/Additions

4.3.3 Duplications

4.3.4 Replacements

4.3.5 Regression

4.4 Toponyms considered ‘classically’ Greek

4.5 Cretan toponyms

4.6 Toponyms of Attica

4.7 Names of Islands

4.8 ‘Primordial’ names

4.9 Is it ‘pre-Greek’ or ‘Old-Greek?’

4.10 Thracians and Carians

4.11 The Phoenician-Minoan connection

4.12 A Northern (IE) origin of Greek religion

5. Further discussion

5.1 Kurgan Hypothesis

5.1.1 Mounted horses

5.1.2 Wheels and chariots

5.2 Krahe’s hydronyms

5.3 Neolithic Continuity

5.4 The European Megalithic

5.5 The Younger Dryas phenomenon

6. Appendices

6.1 Cultural assimilation

6.1.1 The phenomenon of acculturation

6.1.2 A memetic origin of language

6.1.3 Modern relative gene research

6.2 Symbolic representations

6.2.1 Archetypal origins

6.2.2 The horse and the wheel

6.2.3 The bear and the wolf

6.2.4 Psychic twins

6.3 Fundamental symmetries

6.3.1 Satem- Centum symmetry

6.3.2 Non- locality in evolution

7. Conclusions

8. Epilogue

9. Notes

1. Prologue

1.1 About Strabo’s geography

Strabo (64 or 63 BCE- 24 CE) was born in Amasya, Pontus, in North Asia Minor (modern Turkey). He started writing his Geography (Geographica) about 20 BCE and went on reediting it till his death. With the exception of a few missing parts, it has come down to us complete.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strabo]

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geographica]

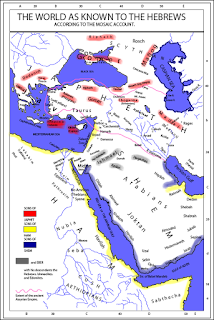

The previous map was handed down to Strabo from previous geographers, such as Eratosthenes or Hecataeus. We need not comment on the poor knowledge of the world at that time, except perhaps note the characteristic peculiarity of the Taurus mountain range which is depicted on the map stretching from Asia Minor to the extremities of the then known world in Asia. This is interesting because it creates a very distinct line between two worlds, that of the ‘North’ and that of the ‘South.’ In the North there are Parthians and Scythians, Thracians and Phrygians, and the Celts of Europe, all the ‘white’ tribes. In the South there are the Indians, the Egyptians and Mesopotamians, the Ethiopians and the rest of the Libyans (Africans), the ‘dark’ peoples. I believe this division, although crude, is interesting because it forms an analogy with the modern distinction between the Indo-Europeans (IEs) of the ‘North’, versus the non- IEs of the ‘South.’ However Strabo’s approach may be found to be more clarifying with respect to the formation of the first languages- such as Greek, Latin, and perhaps the so called Luwian languages of Asia Minor (Lycian, Lydian, Carian, and so on)- because of both its simplicity and its proximity to the spoken languages of the time.

1.2 Purpose of this survey

Scholars have found that toponyms provide valuable insight into the historical geography of a particular region. Powicke said of place-name study that it “uses, enriches and tests the discoveries of archaeology and history and the rules of the philologists.” Toponyms not only illustrate ethnic settlement patterns, but they can also help identify discrete periods of immigration.

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toponymy]

The purpose of this study is to classify all toponyms found in the Geography (those concerning India, Africa and Arabica will be added in the future) in order to trace back as far as possible their origin, as well as to discover any changes that took place. The survey will be centered on the Hellenistic world (which at Strabo’s time was under Roman rule). Strabo’s geography includes the knowledge of many previous Greek writers, such as Eratosthenes, therefore it offers an excellent opportunity to study through toponyms the influences of other (the so called pre-Indo-European) languages on the Greek language (considered Indo-European). This is important not just in the narrow context of the Greek language but also with respect to the broader field concerning the interactions between IE and non IE languages such as Phoenician, ancient Egyptian, Luwian (which may be considered of mixed origin), or Minoan (probably of Luwian origin but which remains undeciphered.)

1.3 The scenery

(The ancient East Mediterranean up to Strabo’s time)

Migrations in Anatolia around 1,900 BCE based on outdated research. According to Drews and Mellart, the Hittite migration displaced other peoples living in Anatolia, who in turn displaced the Middle Helladic Greek-speaking peoples to the west. This is contradicted by newer research.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Bronze_Age_migrations_(Ancient_Near_East)]

One of the researches which Wikipedia refers to is that of Russell D. Gray and Quentin D. Atkinson (2003). Analyzing linguistic data with computational methods derived from evolutionary biology these researchers came down with an initial Indo-European divergence of between 7,800 and 9,800 years BP (about 7,000 BCE).

[https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/10655/nature02029.pdf%3Fsequence%3D3]

This time would coincide with the first Neolithic settlements in Greece, implying that the IE languages (at least their first substrata) came in Europe with the Neolithic Revolution. Currently it is believed that the first Indo-Europeans arrived in Greece during or just before the appearance of the Mycenaean civilization, in the first half of the second millennium BCE. Previously it was thought that the first Greeks had arrived during the so called Dorian invasion at the end of the Bronze Age, about 1,200 BCE. But the decipherment of the Mycenaean Linear B showed that its language was Greek. It seems that newer researches tend to push the date for the arrival, if there was any arrival at all, of the Greeks further back in earlier times.

As far as the Hittites are concerned their appearance is important because they are considered the first IEs who left behind written records. Their capital was named Hatussa, in central Anatolia, a name borrowed from the Hattians, the previous inhabitants of the area, probably of Caucasian origin. It is known that the Hittite language was heavily influenced by the local Anatolian languages. We might suppose that the Luwian IE branch formed during this period but it is more likely that Luwian had already existed in Anatolia before the Hittites came. For example, the name of the first Hittite ruler, Hattusili I, has a suffix –li which is common even today in Caucasian names and which was probably common in Anatolia at that time, as it is in modern Anatolia (Turkey) in the form –ali. Another example is the name the Hittites used for Miletus (Greek Milētos, Turkish: Milet), Millawanda. Miletus was in ancient Lycia and the name the Lycians used for themselves (at least at the time of ancient Greece) was something like Trimili or Termili (or perhaps Milla). Therefore the words Milētos and Milawanda could be paraphrases of the name the Lycians used for this city in the native language. So it seems that the IEs formed a super stratum on local Luwian languages in Anatolia instead of composing them.

Erroneously enough the suffix –anda is considered IE for the Hittites but not for the Greeks in cases such as Corinth (Greek: Corinthos), And(r)os (a Greek island), or even Hellas or Ella(n)da. The Greek vocabulary is full of these words (many of which are not place names) whose suffix is more or less of the same morphology as the Hittite –anda or even the modern –and which is found in Germanic languages (the word Switzerland for example). We will talk more about this later on.

1.4 The world of the Pelasgians

Ancient regions of Anatolia (500 BCE)

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatolia]

The term Pelasgian should be considered a generic term, although it may denote the people that used to live in the Pelasgic Argos, modern Thessaly. As Strabo says, “And that portion of Thessaly between the outlets of the Peneius and the Thermopylæ, as far as the mountains of Pindus, is named Pelasgic Argos, the district having formerly belonged to the Pelasgi.”

Strabo also says, “Almost everyone is agreed that the Pelasgi were an ancient race spread throughout the whole of Greece, but especially in the country of the Aeolians near to Thessaly.”

Therefore it seems that before the Greeks there were the Pelasgi, although it seems that the Greeks could have evolved from a specific Pelasgian branch somewhere in Thessaly. According to the mainstream IE theory, the Greeks are supposed to have arrived in Greece from the North, either from the Balkans or from North Asia Minor (or from both places), coming from their ultimate homeland in the Pontic steppes (in modern day Ukraine). However the story told by the ancient Greek writers themselves is quite different. With respect to Cadmus (the founder of Thebes in Greece) Strabo says,

“Bœotia was first occupied by Barbarians, Aones, and Temmices, a wandering people from Sunium, by Leleges, and Hyantes. Then the Phœnicians, who accompanied Cadmus, possessed it. He fortified the Cadmeian land, and transmitted the government to his descendants. The Phœnicians founded Thebes, and added it to the Cadmeian territory. They preserved their dominion, and exercised it over the greatest part of the Bœotians till the time of the expedition of the Epigoni (in Mycenaean times). At this period they abandoned Thebes for a short time, but returned again. In the same manner when they were ejected by Thracians and Pelasgi, (during the Greek Dark Ages?) they established their rule in Thessaly together with the Arnœi for a long period, so that all the inhabitants obtained the name of Bœotians. They returned afterwards to their own country, at the time the Æolian expedition was preparing at Aulis in Bœotia which the descendants of Orestes were equipping for Asia.”

As far as Danaus is concerned, Strabo says, “Danaus is said to have built the citadel of the Argives. He seems to have possessed so much more power than the former rulers of the country, that, according to Euripides, he made a law that those who were formerly called Pelasgiotæ, should be called Danai throughout Greece. His tomb, called Palinthus, is in the middle of the marketplace of the Argives. I suppose that the celebrity of this city was the reason of all the Greeks having the name of Pelasgiotæ, and Danai, as well as Argives.”

From this narration we see how much complicated the story about the Pelasgi is. If Cadmos and Danaus were Phoenicians, who incidentally could have been first cousins, sons of the brothers Agenor and Belos respectively, it is obvious that we should reconsider the foundation of the Mycenaean civilization. Was it founded by IEs who came from the North or from Asia Minor or by Semites from the Levant? It is also interesting to note that when Danaus came to Argos, the city at the time was ruled by King Pelasgus, who was called Gelanor. The Danaides asked Pelasgus for protection when they arrived, the event portrayed in The Suppliants by Aeschylus. Protection was granted after a vote by the Argives.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danaus]

Was the Mycenaean civilization founded by incoming Semites who joined indigenous Pelasgians? Or could the names of Agapenor and Gelanor be of IE origin, and that both Cadmos and Danaus were IEs having conquered places in Egypt and Phoenicia, and then in Greece? We should also note that the names of their wives seem to be of local (Pelasgian) origin, Armonia and Pieria respectively. Do the origin of names imply the origin of power shift in this strange brew of many different peoples? Certainly yes, but we should also take into account that all these names survived through Greek mythology, not Egyptian or Phoenician. Therefore the names are already Hellenized (the name Belos for example could be Baal in Phoenician, and so on). But again the morphology of the names and their corresponding history give clues about their origin and their whereabouts.

Pelops for example is said to have come from Phrygia, according to Strabo. He also says, “It is said that the Achæan Phthiotæ, who, with Pelops, made an irruption into Peloponnesus, settled in Laconia, and were so much distinguished for their valor, that Peloponnesus, which for a long period up to this time had the name of Argos, was then called Achæan Argos; and not Peloponnesus alone had this name, but Laconia also was thus peculiarly designated.” Therefore Pelops on the contrary to Cadmus and Danaus came from the North.

Cecrops who built the Cecropian walls in Athens could be of the same stock as Pelops. According to Strabo, “It will suffice then to add, that, according to Philochorus, when the country was devastated on the side of the sea by the Carians, and by land by the Bœotians, whom they called Aones, Cecrops first settled a large body of people in twelve cities, the names of which were Cecropia, Tetrapolis, Epacria, Deceleia, Eleusis, Aphidnæ, Thoricus, Brauron, Cytherus, Sphettus, Cephisia [Phalerus]. Again, at a subsequent period, Theseus is said to have collected the inhabitants of the twelve cities into one, the present city.”

It is interesting to add that Tantalus, the father of Pelops, is referred to as ‘Phrygian,’ and sometimes even as ‘King of Phrygia,’ although his city was located in the western extremity of Anatolia where Lydia was to emerge as a state before the beginning of the first millennium BCE, and not in the traditional heartland of Phrygia, situated more inland. References to his son as ‘Pelops the Lydian’ led some scholars to the conclusion that there would be good grounds for believing that he belonged to a primordial house of Lydia.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tantalus ]

Thus it seems that newcomers, supposedly in the beginning and during the Mycenaean times, came to Greece, some of which were conquerors, establishing their rule on the Pelasgic population of Greece. This population would be the offspring of the first Neolithic farmers. The newcomers (either conquerors or migrants), according to the legends and to Strabo’s narration, came both from the Balkans and from Anatolia. The names of the conquerors suggest an IE origin (if we consider the Phrygians or Thracians IEs). But the Pelasgi who came into Greece from Anatolia (Temmices and Leleges for example) were also IEs (Lycians or Lydians or Carians). Although it seems that for a long time places in Greece had been occupied by non- Greek speaking populations (e.g. according to Strabo’s narration Thebes was liberated from the Phoenicians in late Mycenaean times), names such as Armonia and Pieria (the names of the wives of Cadmus and Danaus) suggests that the Greek language was already spoken in Greece in some form (‘Armonia’ sounds much more Greek than ‘Cadmus.’ Therefore even if we consider IE conquerors during Mycenaean times in Greece, they didn’t replace the language, although they may well have added plenty new words to the overall vocabulary.

2. Stabo’s toponyms by place

2.1 Iberia

Strabo begins his Geography from the West to the East, from Iberia. He considers the Pyrenees the dividing line between Iberia and Keltica (Gaul). He mentions the Sacred Promontory and the Pillars of Hercules (Straits of Gibraltar) and he says that “(according to Artemidorus) there is no temple of Hercules shown there, as Ephorus falsely states, nor yet any altar [to him] nor to any other divinity; but in many parts there are three or four stones placed together, which are turned by all travelers who arrive there, in accordance with a certain local custom, and are changed in position by such as turn them incorrectly.”

Place names

| Πυρήνη | Pyrene | Mountain (Pyrenees) |

| Τάγος | Tagos | River |

| Ἄνας | Anas | River (Guadiana) |

| Βαῖτις | Baetis | River (Guadalquivir) |

| Κάλπη | Calpe | Mountain/city (Calp) |

| Καρτηία | Carteia | City |

| Μελλαρία | Mellaria | City (perhaps Tarifa) |

| Βελὼν | Belon | City and river |

| Γάδειρα/Ἐρύθεια) | Gadeira/Erytheia) | City (Cádiz) |

| Ἄστα | Asta | City |

| Νάβρισσα/Νέβρισσα | Nabrissa/Nebrissa | City (Lebrija) |

| Ἐβοῦρα | Ebura | City (Évora) |

| Κόρδυβα | Corduba | City (Córdoba) |

| Ἷσπαλις | Hispalis | City (Seville) |

| Ἰτάλικα | Italica | City |

| Ἴλιπα | Ilipa | City |

| Ἄστιγις | Astygis | City (Écija) |

| Κάρμων | Carmon | City (Carmona) |

| Ὀβούλκων | Obulcon | City (Porcuna) |

| Μοῦνδα | Munda | City |

| Ἀτέγουα | Ategua | City |

| Οὔρσων | Urson | City |

| Τοῦκκις | Tukkis | City |

| Οὐλία | Julia | City |

| Αἴγουα | Aegua | City |

| Σισάπων | Sisapon | City |

| Κωτίναι | Cotinae | Mountain |

| Ὄνοβα | Onoba | City (Huelva) |

| Ὀσσόνοβα | Ossonoba | City (Faro) |

| Μαίνοβα | Maenoba | City |

| Γυμνησίαι/Βαλιαρίδαι | Gymnesiae/Balearidae | Islands (Majorca and Minorca) |

| (Νέα) Καρχηδὼν | (Nea) Karchedon | City |

| Ὀδύσσεια | Odysseia | City |

| Τάρτεσσος | Tartessos | City (according to Strabo identified with Carteia) |

| Μόρων | Moron | City |

| Ὀλυσιπὼν | Olysipon | City |

| Δούριος | Dourios | River |

| Ἀκούτεια | Akouteia | City |

| Καστουλὼν | Castulon | City (Castellón) |

| Μούνδας | Moundas | River (Mondego) |

| Ὀυακούας | Vakouas | River (Vouga) |

| Λήθη/Λιμαίας/Βελιὼν | Lethe/Limaeas/Velion | River |

| Βαῖνις/Μίνιος | Baenis/Minios | River |

| Νέριον | Nerion | Promontory |

| Ἴβηρας | Iberas | River (Ebro) |

| Μάλακα | Malaca | City (Málaga) |

| Μαινάκα | Maenaca | City |

| Ἄβδηρα | Abdera | City |

| Ὠκέλλα | Ocella | City |

| Σούκρων | Sucron | City/river (Júcar) |

| Πλανησία | Planesia | Island |

| Πλουμβαρία | Plumbaria | Island |

| Σκομβραρία | Scombraria | Island |

| Σάγουντος | Saguntos | City |

| Χερρόνησος | Cherronessus | City |

| Ὀλέαστρον | Oleastron | City |

| Καρταλίας | Cartalias | City |

| Δέρτωσσα | Dertossa | City |

| Ταρράκων | Taraccon | City |

| Ἡμεροσκοπεῖον | Hemeroscopion | City |

| Ἔβυσος | Ebusus | Island (Ibiza) |

| Ἐμπορίον | Emporion | City |

| Ῥόδη | Rhode | City |

| Σαίταβις | Setabis | City |

| Ἐγελάσται | Egelastae | City |

| Ἰδουβέδα | Idubeda | Mountain |

| Ὀροσπέδα | Orospeda | Mountain |

| Καισαραυγοῦστα/Κέλσα | Caesaraugusta/Celsa | City |

| Ἰλέρδα | Ilerda | City |

| Ὄσκα | Osca | City |

| Καλάγουρις | Calaguris | City |

| Πομπέλων | Pompelon | City |

| Αὐγοῦστα Ἠμερίτα | Augusta Emerita | City |

| Μέλσος | Melsus | River |

| Νοῖγα | Nouga | City |

| Πιτυούσσαι | Pityusae | Islands (Ibiza and Fromentera) |

| Ὀφιοῦσσα | Ophiussa | Island (Fromentera) |

| Πάλμα | Palma | City |

| Πολεντία | Polentia | City |

| Διδύμη | Didyme | City |

| Καττιτερίδες | Cassiterides | Islands (according to Strabo other than Great Britain) |

There is an apparent connection between the Iberian Peninsula and Phoenicians as shown by place names such as Gadeira (Phoenician: Cadir), Córdoba (Carthaginian: Kartuba), Málaga, Onoba, etc. But there are also elements which suggest not only Phoenician, or Greek contacts, but also contacts of a pre- Phoenician and pre- Greek origin; that is earlier than the supposed voyage of Hercules to these places.

An intriguing example is the city (also island) of Ebusus. It is modern Ibiza (one of the ancient Pityusic islands). In Catalan: Eivissa, in Phoenician: Yibosim. Strabo calls the place Ebusos. One might consider the name Phoenician but in fact the Phoenicians arrived there just in 654 BCE.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibiza]

The clue is found in the suffix –(i)ssa of the word in the native Catalan language (Eivissa). It is also attested that the islands were used by Cilician pirates as a base during the Roman times, before the Romans drove them away.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pityusic_Islands]

Those suffixes are common in Greece and Asia Minor and they are related to the Luwian language of ancient Anatolia (where Cilicia was found). Therefore neither the Greeks nor the Phoenicians were the first who arrived as far as the straits of Gibraltar in prehistoric times. But apparently both the Greeks and the Phoenicians, and after them the Romans and the Spanish, borrowed the names. These names therefore have to do with the earlier sub- stratum of place names around the Mediterranean, a local isogloss which was borrowed both by Indo-Europeans (such as the Romans and the Greeks) and by Semites (such as the Phoenicians and the Arabs).

To go a step further, I would like to make an interesting connection regarding the Greek city of Ephesus (modern Efes, Turkey) in Asia Minor. The Hittites, who inhabited the area during the 2nd millennium BCE called the city Abasa, which they referred to as capital of Arzawa. The connection between the Arzawans of the Hittites and the Argives of Homer is very tantalizing. Were these the Argives, or Arzawans, the people who settled in Argos, Greece, with Danaus or whoever was their leader? Whatever the answer, the point is that the area surrounding Ephesus was already inhabited during the Neolithic Age (about 6,000 BCE).

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ephesus]

And this is a period much earlier than any division between Semites and Indo-Europeans, Phoenicians and Greeks. This is why some people, like Collin Renfrew, have placed the birth place of IE languages in Ancient Anatolia during the Neolithic, not in the Caspian steppes during the Eneolithic or Bronze Age. Wherever the motherland of IEs, it seems that ancient Anatolia played a pivotal role in the blending of languages and people who would later form the civilizations of Phoenicia, Greece, and Rome. I would later expose some arguments why I believe that ancient Anatolia was a place where IE and Semitic languages converged, but it was not the motherland of either language group.

2.2 Keltiberia

(Above the Ebro river)

place names

| Ὀυαρία | Varia | City |

| Νομαντία | Numantia | City |

| Σεγήδα | Segeda | City |

| Παλλαντία | Palantia | City |

| Σεγοβρίγα | Segobriga | City |

| Βίλβιλις | Bilbilis | City |

| Σεγεσάμα | Segesama | City |

| Ἰντερκατία | Intercatia | City |

2.3 Keltica

Strabo describes Keltica as the land beyond the Alps which consisted of three nations, “Aquitani, Belge, and Kelte. Of these the Aquitani differ completely from the other nations, not only in their language but in their figure, which resembles more that of the Iberians than the Galatae. The others are Galatae in countenance, although they do not all speak the same language, but some make a slight difference in their speech…”

Place names

| Μασσαλία | Massalia | City (Marseille) |

| Κέμμενον | Cemmenon | Mountain (Cévennes) |

| Ῥοδανὸς | Rodanos | River (Rhone) |

| Ὀυᾶρος | Varos | River (Var) |

| Νάρβων | Narbon | City (Narbonne) |

| Νέμαυσος | Nemausos | City (Nîmes) |

| Οὐγέρνοςπολις | Antipolis | City |

| Δρουεντία | Druentia | City |

| Καβαλλίων | Caballion | City |

| Ἐβρόδουνον | Ebrodunon | City |

| Βριγάντιον | Brigantion | City |

| Σκιγγομάγος | Scingomagos | City |

| Ὤκελον | Ocelon | City |

| Ῥόη | Rhoa | City |

| Ἀγάθη | Agathe | City |

| Ταυροέντιον | Tauroention | City |

| Ὀλβία | Olbia | City |

| Νίκαια | Nicaea | City |

| Ἀβεντίνον | Aventinon | Mountain |

| Σήτιον | Setion | Mountain |

| Βλάσκων | Blascon | Island |

| Ἀρελᾶτε | Arelate | City |

| Ἀφροδίσιον | Aphrodision | Promontory |

| Ῥουσκίνων | Ruscinon | River/city |

| Ἰλίβιρρις | Ilibirris | River/city (Elne) |

| Ἄταξ | Atax | River (Aude) |

| Ὄρβις | Orbis | River (Orbre) |

| Ἄραυρις | Rauraris | River (Hérault) |

| Βαίτερρα | Baetera | City |

| Ταυροέντιον | Tauroention | City |

| Φόρον Ἰούλιον | Foron Ioulion | Port |

| Στοιχάδες | Stoechades | Islands |

| Πλανασία | Planasia | Island |

| Λήρων | Leron | Island |

| Ὀξυβίων | Oxibius | Port |

| Δρουεντίας | Durance | River |

| Ἴσαρ | Isar | River |

| Σούλγας | Sulgas | River |

| Οὔνδαλον | Undalon | City |

| Αὐενιὼν | Avenion | City |

| Ἀραυσίων | Arausion | Arausion |

| Ἀερία | Aeria | City |

| Ὀυίεννα | Vienna | City (Vienna) |

| Λούγδουνον | Lugdunon | City (Lyon) |

| Ἄραρ | Arar | River (Saône) |

| Λημέννη | Lemenne | Lake (Lake Geneva) |

| Δοῦβις | Doubis | River (Doubs) |

| Ἄγκυρα | Agyra | City |

| Τολῶσσα | Toulouse | City |

| Λίγηρ | Loire | River |

| Γαρούνας | Garrone | River |

| Βουρδίγαλα | Burdigala | City |

| Κορβιλὼν | Corbilon | City |

| Μεδιολάνιον | Mediolanion | City |

| Νέμαυσος | Nemausos | City |

| Γαλατικὸς | Galaticos | Gulf (Galatic gulf) |

| Νεμωσσὸς | Nemossos | City |

| Κήναβον | Kenabon | City |

| Γεργοουία | Gergouvia | City |

| Ἀλησία | Alesia | City |

| Ῥήνος | Renos | River (Rhine) |

| Σηκοάνας | Secoanas | River (Seine) |

| Καβυλλῖνον | Cabyllinon | City |

| Βίβρακτα | Bibracta | City |

| Ἀδούλα | Adula | Mountain |

| Ἀδούας | Aduas | River |

| Λάριος | Larios | Lake |

| Κῶμον | Comon | City (Como) |

| Πάδος | Pados | River (Po) |

| Ἰουράσιος | Iurasios | Mountain (Jura) |

| Ἀρδουέννα | Arduenna | Forest |

| Λουκοτοκία | Lucotocia | City |

| Δουρικορτόρα | Duricortora | City |

| Ἴτιον | Ition | City |

| Δουρίας | Durias | River |

2.4 The Alps

(Around the mountain range)

Place names

| Ἄλπεις/Ἄλπεια/Ἄλβια/Ἀλπεινά | Alpeis/Alpeia/Albia/Alpeina | Mountain (Alps) |

| Σαβάτων ὀυάδα | Sabaton Uada | City |

| Ἀλβίγγαυνον | Albigaunon | City |

| Ὄκρᾳ | Ocra | Mountain (part of the Alps) |

| Ἄλβιον | Albion | Mountain (part of the Alps) |

| Ἀδούλας | Adulas | Mountain |

| Κώμον | Comon | City (Como) |

| Ποινίνος | Poeninos | Mountain (Pennine Alps) |

| Μουτίνη | Mutina | City (Modena) |

| City (Modena) | Eporedia | City (Ivrea) |

| Οὐήρων | Ueron | City (Verona) |

| Καμβόδουνον | Campodunum | City |

| Δαμασία | Damasia | City |

| Ἀτησῖνος | Atesinos | River |

| Ἴστρος | Istros | River (Danube, lower part) |

| Ἑρκυνίος | Ηercynios | Forest |

| Τοῦλλον | Tullon | City |

| Φλιγαδία | Phligadia | City |

| Δούρας | Duras | River |

| Κλάνις | Clanis | River |

| Μέτουλον | Metulon | City |

| Ἀρουπῖνοι | Arupinoi | City |

| Μονήτιον | Monetion | City |

| Ὀυένδων | Vendon | City |

| Σεγεστικὴ | Segestike | City |

| Σάβος | Sabos | River (Save) |

| Ἀκυληία | Aquleia | City |

| Κορκόρας | Korkoras | River |

| Κόλαπις | Kolapis | River |

| Βήνακος | Benacos | Lake |

| Μίγκιος | Migios | River |

| Ὀυερβανὸς | Verbanos | Lake |

| Τικῖνος | Ticinos | River |

| Λάριος | Larios | Lake |

| Ἀδούας | Aduas | River |

2.5 Britain

About Britain there was little known at the time of Strabo. Most of the knowledge came from legends and from the Roman expeditions. Kent is the only city that Strabo refers to, while Ierna and Thule are referred to as mythical places.

Place names

| Κάντιον | Kantion | City (Kent) |

| Ἰέρνη | Ierne | Island (probably Ireland, also attested as Hibernia) |

| Θούλη | Thule | Island (mythical place, possibly related to Denmark or Scandinavia) |

2.6 Italy

Concerning Italy Strabo says, “At the foot of the Alps commences the region now known as Italy. The ancients by Italy merely understood Œnotria, which reached from the Strait of Sicily to the Gulf of Taranto, and the region about Posidonium, but the name has extended even to the foot of the Alps… It seems probable that the first inhabitants were named Italians, and, being successful, they communicated their name to the neighboring tribes, and this propagation [of name] continued until the Romans obtained dominion. Afterwards, when the Romans conferred on the Italians the privileges of equal citizenship, and thought fit to extend the same honor to the Cisalpine Galatæ and Heneti, they comprised the whole under the general denomination of Italians and Romans.”

Place names

| Οἰνωτρία | Oenotria | Ancient name of Italy |

| Ναύπορτος | Nauportos | City |

| Μονοίκος | Monoecos | Port |

| Γενούα | Genua | City (Genoa) |

| Ἀπέννινα | Apennina | Mountain (Apennines) |

| Ἀδριατικὴ | Adriatike | Sea (Adriatic) |

| Τυρρηνικὴ/Τυρρηνία | Tyrrhenike/Tyrrhenia | Sea (Tyrrhenian) |

| Πόλα | Pola | City |

| Σικελία | Sicelia | Island (Sicily) |

| Αριμίνον | Ariminon | City |

| Ῥαουέννη | Rauenne | City (Ravenna) |

| Ἀγκῶνας | Agonas | City (Ancona) |

| Πῖσα | Pisa | City |

| Ταραντῖνος | Tarantinos | Gulf (Taranto) |

| Ποσειδωνία | Posidonia | Promontory (Paestum) |

| Λευκόπετρα | Leucopetra | City |

| Ῥηγίνη/ Ῥηγίον | Regine/Region | City (Reggio) |

| Βριξία | Brescia | City |

| Μάντουα | Mantua | City |

| Πατάουιον | Patavion | City (Padua) |

| Μεδόακος | Medoacos | Harbor/river |

| Ἀλτῖνον | Altinon | City |

| Βούτριον | Butrium | City |

| Σπῖνα | Spina | City |

| Οπιτέργιον | Opitergion | City |

| [Κωνκ]ορδία | Concordia | City |

| Ἀτρία | Atria | City |

| Ὀυικετία | Vicetia | City |

| Νατίσωνας | Natisonas | River |

| Νωρηία | Noreia | City |

| Τίμαυον | Timavon | Harbor/River |

| Ἄργος τὸ Ἷππιον | Argos-Ippion | City |

| Τεργέστη | Tergeste | City |

| Τίβερις | Tiberis | River (Tiber) |

| Πλακεντία | Placentia | City |

| Κρεμώνη | Cremone | City |

| Πάρμα | Parma | City |

| Βονωνία | Bononia | City |

| Ἄγκαρα | Acara | City |

| Ῥήγιον- Λέπιδον | Rhegion-Lepidon | City |

| Μακροὶ Κάμποι | Macroe-Campoe | City |

| Κλάτερνα | Claterna | City |

| Φόρον Κορνήλιον | Forum-Cornelium | City |

| Φαουεντία | Faventia | City |

| Καισήνα | Caesena | City |

| Σάπιος | Sapios | River (Savio) |

| Ρουβίκων | Rubicon | River |

| Κόττιος | Cottios | Mountain |

| Κλαστίδιον | Clastidion | City |

| Δέρθων | Derthon | City |

| Ἀκουαιστατιέλλαι | Aquae-Statiellae | City |

| Λούνη | Lune | City |

| Τρεβίας | Trebias | River |

| Αἶσις | Aesis | River (Esino) |

| Σκουλτάννας | Scultannas | River (Panaro) |

| Ὀυερκέλλοι | Vercelloe | Village (Vercelli) |

| Σαρδηνία | Sardinia | Island |

| Σινοέσσα | Sinoessa | City |

| Ὤστια | Ostia | Port |

| Σαυνιτικά | Saunitica | Mountains |

| Ταρκυνία | Tarquinia | City |

| Ῥώμη | Rome | City |

| Κλούσιον | Clusion | City (Clusium) |

| Ἄγυλλα | Agylla | City (afterwards Caerea, modern Cerveteri) |

| Ὀυολατέρραι | Volaterae | City (Volterra) |

| Ποπλώνιον | Poplonion | City |

| Κόσα | Cossa | City |

| Σελήνη | Selene | City |

| Μάκρας | Macras | River |

| Ἄρνος | Arnos | River (Arno) |

| Αὔσαρ | Ausar | River (Esaro) |

| Ἀρρήτιον | Arretion | Mountain |

| Κύρνος | Cyrnos | Island (Corsica) |

| Αἰθαλία | Aethalia | Island (Elba) |

| Ἀργῷος | Argoios | Port |

| Βλησίνων | Blesinon | City |

| Χάραξ | Charax | City |

| Ἐνικονίαι | Eniconiae | City |

| Ὀυάπανες | Vapanes | City |

| Κάραλις | Caralis | City |

| Σοῦλχοι | Sulchoe | City |

| Κόσαι | Cossae | City |

| Γραουίσκοι | Gravisci | City |

| Πύργοι | Pyrgoe | City |

| Ἄλσιον | Alsion | City |

| Φρεγῆνα | Fregena | City |

| Ῥηγισουίλλα | Regis-Villa | City |

| Περουσία | Perusia | City |

| Ὀυολσίνιοι | Volsinioe | City |

| Σούτριον | Sutrion | City |

| Βλήρα | Blera | City |

| Φερεντῖνον | Ferentinon | City |

| Φαλέριοι | Falerion | City |

| Φαλίσκον | Faliscon | City |

| Νεπήτα | Nepita | City |

| Στατωνία | Statonia | City |

| Σωράκτις | Soracte | Mountain |

| Φερωνία | Feronia | City |

| Κιμινία | Ciminia | Lake |

| Σαβάτα | Sabata | Lake |

| Τρασουμέννα | Trasumenna | Lake |

| Σάρσινα | Sarsina | City |

| Σήνα | Sena | City |

| Μάρινον | Marinon | City |

| Κίγγουλον | Cingulon | Mountain |

| Σεντῖνον | Sentinon | City |

| Μέταυρος | Metauros | River |

| Ὀκρίκλοι | Ocricli | City |

| Κάρσουλοι | Carsuloe | City |

| Μηουανία | Mevania | City |

| Τενέας | Teneas | River |

| Λαρολόνοι | Larolonoe | City |

| Ναρνία | Narnia | City |

| Νὰρ | Nar | River (Nera) |

| Φόρον Φλαμίνιον | Forum Flaminium | City |

| Νουκερία | Nuceria | City |

| Φόρον Σεμπρώνιον | Forum Sempronium | City |

| Ἰντέραμνα | Interamna | City |

| Σπολήτιον | Spoletion | City |

| Αἴσιον | Aesion | City |

| Καμέρτη | Camerte | City |

| Ἀμερία | America | City |

| Τοῦδερ | Tuder | City |

| Εἰσπέλλον | Hispellon | City |

| Ἰγούιον | Iguvion | City |

| Νωμεντός | Nomentos | City |

| Ἀμίτερνον | Amiternon | City |

| Ῥεᾶτε | Reate | City |

| Κωτιλίαι | Cotyliae | Spring |

| Ἰντεροκρέα | Interocrea | Village |

| Φόρουλοι | Foruloe | Rocks |

| Κύρις | Curis | Village |

| Τρήβουλα | Trebula | Village |

| Ἠρητὸν | Ereton | Village |

| Ἀρδέα | Ardea | City |

| Λαυρεντὸν | Laurenton | City |

| Λαουινία | Lavinia | City |

| Ἄλβα | Alba | City |

| Ἀλβανός | Albanos | Mountain |

| Κολλατία | Collatia | Village |

| Ἀντέμναι | Antemnae | Village |

| Φιδῆναι | Fidenae | Village |

| Λαβικὸν | Labicon | Village |

| Φῆστοι | Festoe | City |

| Ἀπίολα | Apiola | City |

| Σουέσσα | Suessa | City |

| Λανουίον | Lanuvion | City |

| Ἀρικία | Aricia | City |

| Τελλῆναι | Tellenae | City |

| Ἄντιον | Antion | City |

| Κιρκαίον | Circaeon | Mount (Circeo) |

| Στόρας | Storas | River (Stura) |

| Οὔφης/ Αὔφιδος | Ufis/Aufidos | River (Ofanto) |

| Βρεντεσίον | Brendesion | City |

| Φορμίαι | Formiae | City |

| Μιντούρνα | Minturna | City |

| Λεῖρις | Leiris | River (Liri, formely Clanis) |

| Καιάτας | Caeatas | Gulf |

| Φρεγέλλα | Fregella | Village |

| Πανδατερία | Pandataria | Island |

| Ποντία | Pontia | Island |

| Καίκουβον | Caecubon | City |

| Φοῦνδοι | Fundoe | City |

| Καίλιον | Caelion | Hill (Caelian) |

| Ἀβεντῖνον | Aventinon | Hill (Aventine) |

| Κυρῖνον | Quirinon | Hill (Quirinal) |

| Ἠσκυλίνον | Esqulinon | Hill (Esquiline) |

| Ὀυιμινάλις | Viminalis | Hill (Vinimal) |

| Κλάνις | Clanis | River (Chiana) |

| Κασιλῖνον | Casilinon | City |

| Καπύα | Capya | City |

| Τουσκλανὸν | Tusclanon | Mountain |

| Τούσκλον | Tusclon | City |

| Ἄλγιδον | Algidon | City |

| Λαβικανή | Lavicane | City |

| Φερεντῖνον | Ferentinon | City |

| Φρουσινών | Frusinon | City |

| Κόσας | Cosas | River (Cosa) |

| Φαβρατερία | Fabrateria | City |

| Τρῆρος | Treros | River (Sacco) |

| Ἀκουῖνον | Aquinon | City |

| Μέλπις | Melpis | River (Melfa) |

| Κασῖνον | Casinon | City |

| Τέναον | Teanon | City |

| Καληνῶν | Calenon | City (Cales) |

| Σητία | Setia | City |

| Σιγνία | Signia | City |

| Πρίβερνον | Privernon | City |

| Κόρα | Cora | City |

| Τραπόντιόν | Trapontion | City |

| Ὀυελίτραι | Velitrae | City |

| Ἀλέτριον | Aletrion | City |

| Γάβιοι | Gabioe | City |

| Πραινεστός | Praenestos | City (Palestrina) |

| Καπίτουλον | Capitulon | City |

| Ἀναγνία | Anagnia | City |

| Κερεᾶτε | Cereate | City |

| Σῶρα | Sora | City |

| Ὀυέναφρον | Venafron | City |

| Ὀυουλτοῦρνος | Vulturnos | River |

| Αἰσερνία | Aesernia | City |

| Ἀλλιφαὶ | Alliphae | City |

| Τιβούρων | Tiburon | City |

| Ὀυαρία | Valeria | City |

| Καρσέολοι | Carseoli | City |

| Κούκουλον | Cuculon | City |

| Ἀνίων | Anion | River (Teverone) |

| Ἄλβουλα | Albula | Spring |

| Λαβανά | Labana | Spring |

| Ὀυέρεστις | Verestis | River |

| Ἄλγιδον | Algidon | Mountain |

| Ἀρτεμίσιον | Artemision | City |

| Ἠγερία | Egeria | Spring |

| Φουκίνα | Fucina | Lake |

| Ἀμενάνος | Amenanus | River |

| Κάστρον | Castron | River |

| Αὔξουμον | Auxumon | City |

| Σεπτέμπεδα | Septempeda | City |

| Πνευεντία | Pneventia | City |

| Ποτεντία | Potentia | City |

| Φίρμον Πικηνόν | Firmon Picenon | City |

| Κάστελλον | Castellon | City |

| Τρουεντῖνος | Truentinos | City/river (Tronto) |

| Καστρουνόουν | Castrunooun | City (Castrum novum) |

| Ματρῖνος | Matrinos | Riverc(Piomba) |

| Ἀδρία | Adria | City |

| Ἄσκλον | Asclon | City (Ascoli Piceno) |

| Κορφίνιον | Corfinion | City (later Italica) |

| Σούλμων | Sulmon | City |

| Μαρούιον | Maruvion | City |

| Τεατέα | Teatea | City |

| Ἄτερνον | Aternon | City |

| Ὄρτων | Orton | City |

| Βοῦκα | Buca | City |

| Σάγρος | Sagros | River (Sangro) |

| Μισηνὸν | Misenon | Promontory |

| Ἀθηναίον | Athenaon | Promontory |

| Λίτερνον | Liternon | City |

| Κύμη | Cyme | City |

| Ἀχερουσία | Acherusia | Lake |

| Βαῖαι | Baeae | City |

| Λοκρῖνος | Locrinos | Gulf |

| Ἄορνος | Aornos | Lake (Avernus) |

| Δικαιαρχεία | Dicaearcheia | City (later Puteoli, modern Pozzuoli) |

| Νεάπολις | Neapolis | City (Naples) |

| Πομπηία | Pompeia | Port |

| Σάρνος | Sarnos | River |

| Ὀυέσουιον | Vesuvion | Mountain (Vesuvius) |

| Αἴτνα | Aetna | Mountain |

| Καπρέα | Caprea | Island |

| Σειρῆναι | Seirenae | Islands (Sirenusas) |

| Προχύτη | Prochyta | Island |

| Πιθηκούσσαι | Pithecussae | Island (ancient Ischia) |

| Λιπαραί | Liparae | Islands (Lipari, formerly Meligunis) |

| Ἐπωπέας | Epomeas | Mountain |

| Καλατία | Calatia | City |

| Καύδιον | Caudion | City |

| Βενεουεντόν | Beneventon | City |

| Κάλης | Cales | City |

| Σουέσσουλα | Suessula | City |

| Ἀτέλλα | Atella | City |

| Νῶλα | Nola | City |

| Ἀχέρραι | Acerroe | City |

| Ἀβέλλα | Abella | City |

| Βοιανὸν | Boianon | Village |

| Αἰσερνία | Aesernia | Village |

| Πάννα | Panna | Village |

| Τελεσία | Telesia | Village |

| Ὀυενουσία | Venusia | Village |

| Μαρκῖνα | Marcina | City |

| Σίλαρις | Silaris | River |

| Πικεντία | Picentia | City |

| Σάλερνον | Salernon | City |

| Λευκωσία | Leucosia | Island |

| Ὑέλα/Ἔλα | Hyela/Ela | City (Ancient Elea, present Velia) |

| Παλίνουρος | Palinuros | Promontory |

| Οἰνωτρίδες | Oenotrides | Islands |

| Πυξοῦς | Pyxus | Promontory, harbour, river |

| Λᾶος | Laos | City/gulf/river |

| Πετηλία | Petilia | City |

| Κρίμισσα | Crimissa | Promontory |

| Χώνη | Chone | City |

| Ἔρυξ | Eryx | City |

| Αἴγεστα | Aegesta | City |

| Γρουμεντὸς | Grumentos | Village |

| Ὀυερτῖναι | Vertinæ | Village |

| Καλάσαρνα | Calasarna | Village |

| Μεταπόντιον | Metapontion | City |

| Ἱππωνιάτης | Hipponiates | Gulf (Vibo Valentia) |

| Σκυλλητικὸς | Scylletikos | Gulf (Squillace) |

| Θουρίοι | Thurioe | City (later Copiae) |

| Κηρίλλοι | Cerilloe | City |

| Τεμέση | Temese | City (Tempsa) |

| Τερῖνα | Terina | City |

| Κωσεντία | Cosentia | City |

| Πανδοσία | Pandosia | City |

| Αχέρων | Acheron | River |

| Μέδμα | Medma | City |

| Σκυλλήτιον | Scylletion | City |

| Καῖνυς | Caenys | Promontory |

| Πελωριάς | Pelorias | Cape |

| Μοργάντιον | Morgantion | City (Morgantina) |

| Ἐπῶπις | Epopis | Hill |

| Ἇληξ | Halex | River |

| Μαμέρτιον | Mamertion | City |

| Σίλας | Silas | Forest |

| Καυλωνία | Caulonia | City |

| Λακίνιον | Lacinion | Promontory |

| Κρότων | Kroton | City |

| Νέαιθος | Neaethos | River |

| Σύβαρις | Sybaris | City/river |

| Συρακούσσαι | Syracussae | City (Syracuse) |

| Κρᾶθις | Crathis | River |

| Λαγαρία | Lagaria | Fort |

| Ἡράκλεια | Heracleia | City |

| Ἄκιρις | Akiris | River (Agri) |

| Σῖρις | Siris | River/city (Sinni) |

| Λουκερία | Luceria | City |

| Σικελία | Sicelia | Island (Sicily, formerly Trinacria> Thrinacia) |

| Πάχυνος | Pachynos | Headland |

| Λιλύβαιον | Lilybaeon | Headland |

| Μύλαι | Mylae | City |

| Τυνδαρίδα | Tyndaris | City |

| Ἀγάθυρνον | Agathyrnon | City |

| Ἄλαισα | Alaesa | City |

| Κεφαλοίδιον | Cephaloedion | City |

| Ἱμέρα | Himera | City/river |

| Πάνορμος | Panormos | City |

| Καμαρίνα | Camarina | City |

| Ταυρομένιον | Tauromenion | City |

| Νάξος | Naxos | City |

| Μέγαρα | Megara | City (formerly Hybla) |

| Σύμαιθος | Symaethos | River (Giaretta) |

| Ξιφωνία | Xiphonia | Promontory |

| Χάρυβδις | Charybdis | Sea passage |

| Ἴννησα | Inessa | Hill |

| Κατάνη | Catane | City |

| Ὀρτυγία | Ortygia | Island |

| Ἀρέθουσα | Arethusa | Fountain |

| Κεντόριπα | Centoripa | City |

| Ἀκράγας | Acragas | City |

| Ἔννα | Enna | City |

| Γέλα | Gela | City |

| Καλλίπολις | Callipolis | City |

| Σελινοῦς | Selinus | City |

| Νεβρώδη | Nebrode | Mountain |

| Μάταυρον | Matauron | City |

| Θέρμεσσα | Thermessa | Island (afterwards Hiera) |

| Στρογγύλη | Strongyle | Island |

| Διδύμη | Didyme | Island |

| Ἐρικοῦσσα | Ericussa | Island |

| Φοινικοῦσσα | Phoenicussa | Island |

| Εὐώνυμος | Euonymοs | Island |

| Κόσσουρα | Cossura | Island |

| Αἰγίμουρος | Aegimurοs | Island |

| Ἀκάλανδρος | Acalandrοs | River |

| Κεραύνια | Ceraunian | Mountains |

| Βᾶρις | Baris | City (afterwards Veretum) |

| Λευκὰ | Leuca | City |

| Φλέγρα | Phlegra | City |

| Ὑδροῦς | Hydrus | City |

| Σάσων | Sason | Island |

| Ῥοδίαι | Rodiae | City |

| Λουπίαι | Lupiae | City |

| Ἀλητία | Aletia | City |

| Οὐρία | Uria | City (formerly Hyria) |

| Ἐγνατία | Egnatia | City |

| Καιλία | Celia | City |

| Νήτιον | Netion | City |

| Κανύσιον | Canusion | City |

| Ἑρδωνία | Herdonia | City |

| Καλατίας | Calatias | City |

| Βάριον | Barion | City |

| Σιλουίον | Silvion | City |

| Σαλαπία | Salapia | Port |

| Ἀργυρίππα | Argyrippa | City (Arpi) |

| Διομήδειαι | Diomedeiae | Islands (Diomede) |

| Σιποῦς | Sipus | City (formerly Sepius) |

| Δρίον | Drion | Hill |

| Γάργανον | Garganon | Promontory |

| Οὔριον | Urion | City |

| Αἶσις | Aesis | City (Fiumicino) |

| Κάνναι | Cannae | City |

A very interesting example of suffix analysis from the previous vocabulary includes the case of the Tyrrhenians (Etrusans).

According to Wikipedia, the origin of the name is uncertain. It is only known to be used by Greek authors, but apparently not of Greek origin. It has been connected to tursis, also a ‘Mediterranean’ loan into Greek, meaning ‘tower.’ Direct connections with Tusci, the Latin exonym for the Etruscans, from Tursci have also been attempted.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrrhenians]

Probably the name of the Tyrrhenians was a generic term, meaning something like ‘pirates.’ In the modern Greek language there is the word tarsanas, which means ship yard. The close relationship of this word with the word tyrsinos (Tyrrhenian) shows the connection of the Tyrrhenians with the sea. Perhaps the name corsair which is the same as pirate comes from an original Anatolian word, something like ‘curswara’ or so. But in any case the term Tyrrhenian most likely refers to a diverse group of peoples rather than to a specific ethnicity.

A Tyrrhenian/Etruscan/Lydian association has long been a subject of conjecture. The Greek historian Herodotus stated that the Etruscans came from Lydia, repeated in Virgil’s epic poem the Aeneid, and Etruscan-like language was found on the Lemnos stele from the Aegean Sea island of Lemnos. However, recent decipherment of Lydian and its classification as an Anatolian language mean that Etruscan and Lydian were not even part of the same language family. Nevertheless, a recent genetic study of likely Etruscan descendants in Tuscany found strong similarities with individuals in western Anatolia.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lydia]

This again suggests that the Etruscans/Tyrrrhenians found themselves in Lydia, Anatolia, but this was not their original homeland. Herodotus had also placed them in Crestonia, Thrace. Similarly, Thucydides mentions them together with the Pelasgians and associates them with Lemnian pirates and with the pre-Greek population of Attica. Lemnos remained relatively free of Greek influence up to Hellenistic times, and interestingly, the Lemnos stele of the 6th century BCE is inscribed with a language very similar to Etruscan. This has led to the postulation of a ‘Tyrrhenian language group’ comprising Etruscan, Lemnian and Raetic.

The Raetic language was spoken in the Alps. As far as Lydia is concerned the name Sfard or Sard, another name closely connected to the name Tyrrhenian, was the capital city of the land of Lydia. The name preserved by Greek and Egyptian renderings is Sard, for the Greeks call it Sardis and the name appears in the Egyptian inscriptions as Srdn (one of the Sea Peoples).

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sardis]

Very interestingly, the Sardinians call their language ‘lingua s(f)arda.’ As Strabo notes, “For it is said that Iolaus brought hither certain of the children of Hercules, and established himself amongst the barbarian possessors of the island (Sardinia), who were Tyrrhenians. Afterwards the Phœnicians of Carthage became masters of the island, and, assisted by the inhabitants, carried on war against the Romans; but after the subversion of the Carthaginians, the Romans became masters of the whole.”

Again however the term Sfarda is native to the Lydians not to the Etruscans, whose place names as we shall see are of different morphology. Therefore the Etruscans and the Tyrrhenians must have been of a different origin even if at the time when some of the latter passed from Lydia to Sardinia they considered themselves more ‘Lydian.’

The toponyms to be examined are those ending in –(n)na. As the previous map suggests most of the toponyms of ancient Etruria bear such endings. Strabo refers to some of these: Ravenna, Marcina, Mutina, Poplonium (Popluna); also Ariminum (Arimina), “the Pitheci (or monkeys) are called by the Tyrrhenians Arimi,” Clusium (Clevsin/Clevsina), etc.

I have been wondering about toponyms with the suffix –na. The point is that such toponyms are abundant not only in Italy but also in Greece, for example Mycena (Mycenae), Athina (Athens), Rafina, and they are found not only in coastal areas but also deep in the mainland. How are we to interpret the wide distribution of these place names? Should they be related with the coming of IEs or with a pre-existing substratum spread all across the Mediterranean (which the IEs adopted)?

I’ve found an interesting connection between the name of the capital of Lemnos, Myrina, and a queen of the Amazons who had the same name. According to Diodorus Siculus, she led a military expedition in Libya and won a victory over the people known as the Atlantians, destroying their city Cerne; but was less successful fighting the Gorgons (who are described by Diodorus as a warlike nation residing in close proximity to the Atlantians), failing to burn down their forests. During a later campaign, she struck a treaty of peace with Horus, ruler of Egypt, conquered several peoples, including the Syrians, the Arabians, and the Cilicians (but granted freedom to those of the latter who gave in to her of their own will). She also took possession of Greater Phrygia, from the Taurus Mountains to the Caicus River, and several Aegean islands, including Lesbos (Mytilene); she was also said to be the first to land on the previously uninhabited island which she named Samothrace, building the temple there. The cities of Myrina (in Lemnos), possibly another Myrina in Mysia, Mytilene, Cyme, Pitane, and Priene were believed to have been founded by her, and named after herself, her sister Mytilene, and the commanders in her army, Cyme, Pitane and Priene, respectively. Myrina’s army was eventually defeated by Mopsus the Thracian and Sipylus the Scythian; she, as well as many of her fellow Amazons, fell in the final battle.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myrina_(mythology)]

This story suggests that such place names were native to IEs or more generally to people living in the North, around the Black Sea, the north coast of Asia Minor and parts of the Balkans. The Thracians and Scythians who defeated the Amazons were certainly of IE stock. If the suffix is considered IE then the expansion of IEs may have taken place much earlier than expected. Even the Etruscans could be IEs if they are related to Myrina (who according to Herodotus came from the Ukrainian steppes) and the island of Lemnos (where the Etruscan language was spoken). If we also accept the testimony of Thucydides that the Tyrrhenians occupied Athens before the (Mycenaean) Greeks, and that they are is a direct relationship between the Etruscans and (at least some of) the Tyrrhenians, the Greek language could have already been spoken before the Mycenaean times, at least since the beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE. It suffices to say that place names such as Mycena (Mycenae) or Athina (Athens), which still survive in the modern Greek language, contain the same suffix –na. Therefore both the Mycenaean-Greeks and the Etruscan-Tyrrhenians may have been separated from an earlier common language group.

Furthermore the wide distribution of place names with such a suffix both in Italy and Greece, as well as in other places across Europe (e.g. Vienna) and North Africa (e.g. Medina), even in Minoan Crete (e.g. Gortyna), suggests an early expansion of the corresponding languages in the Bronze Age or even in the Neolithic. But is it better to consider a tremendous expansion of IE languages in a shorter period of time, or to propose an isogloss which evolved across the Mediterranean during a longer period, even since the Neolithic, and which successive waves of newcomers, such as the IEs, adopted?

Another hypothesis suggests that the Etruscans stemmed from the Villanovan Culture in Italy (1,100- 900 BCE), which is thought to have abruptly followed the Terramare Culture (1,700–1,150 BCE). The story may be similar to that of Greece and the fall of the Mycenaean Civilization. It was thought that the Greeks had come after the Mycenaeans, but the decipherment of Linear B showed that the Mycenaeans were in fact Greek. Could accordingly the Etruscans be native to Italy and descants of the Terramare Culture, even if their original homeland was further to the East in remote times? The differences between the language and culture of the Etruscans compared to those of the Italics seem to suggest that they were not native to Italy. However, the newcomers may have been the Italics, not the Etruscans, in the same sense that the Mycenaeans would have been invaders, according to some views. If the toponyms in –na are related to queen Myrina of the Amazons, then the ultimate origin of both the Mycenaeans and the Etruscans (together with the Amazons) could be traced as far as the Ukrainian steppes (as Herodotus places the Amazons there). In such a case all these people would have been IEs. If however the ethnic name of the Tyrrhenians is related to Tyros (Tyre) of Phoenicia or Tarsus of Cilicia then the origin of the same people could be very different.

We may then gather some facts concerning the Etruscans/Tyrrhenians,

- In Italy the Etruscans are identified with the Tyrsenians (Etruria/Etrusci/Tusci). Thus the Etruscans can be considered native to Italy and offspring of the Terramare Culture (either directly related or not).

- However not all Tyrrhenians were Etruscans. In ancient Greece the Tyrrhenians were not identified with the Etruscans. Also it seems that the connection between the Tyrrhenians and the Lydians is superficial, because their languages were different.

- Thus probably the Tyrrhenians were a group of various people, while their name can be related either to ‘tursis’ (tower), or to ‘Tarsus’ (the city in Cilicia), or even to Tyre (the Phoenician city).

- Suffix analysis shows that the suffixes (–na) the Etruscans used, not only for place names but also for common names (e.g. the Etruscan name attested in scripts Thefarie Veliunas) belong to the same isogloss which spread all across the Mediterranean.

- Clues which may further support such an idea: Sardinia probably took its name from the ancient capital of Lydia, Sardis (Sfarda), as well as that Sardinians call their language ‘lingua Sfarda.’ The Basques call their language ‘Euscara’ (‘Etruscan’).

- Therefore, in all likelihood, the Tyrrhenians (=sea-farers/corsairs) used to have a considerable distribution in the prehistoric Mediterranean, representing groups of various people, who were later on commonly referred to as Etruscans, Cilicians, Phoenicians, Minoans, and so on.

2.7 Rest of Europe

(except Greece)

Strabo says, “That which remains is, on the east, all the country beyond the Rhine, as far as the Don and the mouth of the Sea of Azof; and, on the south, that which the Danube bounds, lying between the Adriatic and the left shores of the Euxine, as far as Greece and the Sea of Marmora, for the Danube, which is the largest of the rivers of Europe, divides the whole territory of which we have spoken, into two portions.”

Place names

(North of the Danube)

| Τάναϊς | Tanais | River (Don) |

| Μαιώτις | Maeotis | Sea (of Azof) |

| Ποντικὴ/Πόντος | Pontice/Pontos | Sea (Euxine) |

| Προποντίς | Propontis | Sea (of Marmara) |

| Τύρας | Tyras | River (Dniester) |

| Βορυσθένης | Borysthenes | River (Dnieper) |

| Ἄλβις | Albis | River (Elbe) |

| Ἀμασίας | Amasias | River (Ems) |

| Ἑρκύνιος | Ercynios | Forest |

| Βουίαιμον | Buviaemon | City |

| Βίσουργις | Bisurgis | River (Weser) |

| Λουπίας | Lupias | River (Leppe) |

| Σάλας | Salas | Salas |

| Βυρχανίς | Byrhanis | Island |

| Γαβρῆτα | Gadbreta | Forest |

| Βόσπορος | Bosporos | Strait (Bosporus) |

| Κασπία | Caspia | Sea (Caspian) |

| Ῥιπαῖα | Ripaea | Mountain (Riphean) |

| Ἑλλήσποντος | Hellespontos | Strait (Hellespond) |

| Ὑπάνιος | Hypanios | River (Bog) |

| Φᾶσις | Phasis | River (Rioni) |

| Θερμώδων | Thermodon | River (Terme) |

| Ἅλυς | Halys | River (Kisil-Irmak) |

| Αἵμος | Haemos | Mountain (Haemus) |

| Πεύκη | Peuce | Island |

| Μάρισος | Marisos | River (Mureș) |

| Δανούιος | Danuvios | River (Danube, upper part) |

| Ἑρμώνακτος | Hermonaktos | City |

| Νικωνία | Nikonia | City |

| Ὀφιοῦσσα | Ophiussa | City |

| Λευκὴ | Leuce | Island |

| Ὀλβία | Olbia | City |

| Ταμυράκος | Tamyracos | Gulf |

| Καρκινίτης | Carcinites | Gulf |

| Φαναγόρεια | Phanagoreia | City |

| Παντικαπαίον | Panticapaeon | City/Hill |

| Σαπρά | Sapra | Lake |

| Χερρόνησος | Herronesos | City |

| Παρθένιον | Parthenion | City |

| Κτενοῦς | Ktenus | Port |

| Συμβόλων λιμήν | Symbolon limen | Port |

| Θεοδοσία | Theodosia | City |

| Ταυρικὴ | Taurice | Peninsula (Crimea) |

| Ἄμαστρις | Amastris | City |

| Κριοῦ μέτωπον | Criou-metopon | Promontory |

| Κάραμβις | Carambis | Promontory |

| Τραπεζοῦς | Trapezus | Mountain/City |

| Τιβαρανία | Tibarania | City |

| Κολχίς | Colhis | City |

| Κιμμέριον | Cimmerion | Mountain |

| Νύμφαιον | Nymphaeon | City |

| Μυρμήκιον | Myrmecion | City |

| Ἀχίλλειον | Achilleion | City |

| Παλάκιον | Palakion | Fortress |

| Χάβον | Chabon | Fortress |

| Νεάπολις | Neapolis | Fortress |

| Εὐπατόριον | Eupatorion | Fortress |

Place names

(South of the Danube)

| Ῥοδόπη | Rodope | Mountain |

| Πάρισος | Parisos | River |

| Λούγεον | Lugeon | Marsh |

| Κορκόρας | Corcoras | River |

| Δράβος | Drabos | River |

| Νόαρος | Noaros | River |

| Κόλαπις | Colapis | River |

| Σισκία | Siskia | Strong-hold |

| Σίρμιον | Sirmion | Strong-hold |

| Σκάρδων | Scardon | City/river |

| Ἀψυρτίδες | Apsyrtides | Islands |

| Κυρικτικὴ | Cyrictice | Island |

| Λιβυρνίδες | Libyrnides | Islands |

| Ἴσσα | Issa | Island |

| Τραγούριον | Tragourion | Island |

| Φάρος | Pharos | Island |

| Σάλων | Salon | City |

| Πρώμων | Promon | City |

| Νινίας | Ninias | City |

| Σινώτιον | Sinotion | City |

| Ἀνδήτριον | Andeterion | Fortress |

| Δέλμιον | Delmion | City |

| Ἄδριον | Adrion | Mountain |

| Νάρων | Naron | River |

| Κόρκυρα | Corcyra | Island |

| Ῥιζονικὸς | Rizonikos | Gulf |

| Ῥίζων | Rizon | City |

| Δρίλων | Drilon | River |

| Λίσσος | Lissos | City |

| Ἐπίδαμνος | Epidamnos | City |

| Ἀκρόλισσος (Δυρράχιον) | Akrolissos (Dyrrachion) | City |

| Ἄψος | Apsos | River |

| Ἄωος | Aoos | River |

| Ἀπολλωνία | Apollonia | City |

| Λάκμος | Lakmos | River |

| Ἴναχος | Inachos | River |

| Νυμφαῖον | Nympaeon | Hot springs |

| Βυλλιακὴ | Bylliace | City |

| Ὠρικὸν | Orikon | City |

| Ἰόνιος | Ionios | Sea (Ionian) |

| Μάργος/Βάργος | Margos/Bargos | River |

| Ἑόρτα | Heorta | City |

| Καπέδουνον | Capedounon | City |

| Βυζάντιον | Byzantion | City |

| Ἴστρος | Istros | City |

| Τόμις | Tomis | City |

| Κάλλατις | Kallatis | City |

| Βιζώνη | Bizone | City |

| Κρουνοὶ | Krounoe | City |

| Ὀδησσὸς | Odessos | City |

| Ναύλοχος | Naulochos | City |

| Μεσημβρία | Mesembria | City (previously Menebria) |

| Τίριζις | Tirizis | Promontory |

| Αἶνος | Haenos | City (previously Poltymbria) |

| Ἀγχιάλη | Aghiale | City |

| Θυνιὰς | Thynias | City |

| Φινόπολις | Phinopolis | City |

| Ἀνδριακή | Andriace | City |

| Σαλμυδησσός | Salmydessos |

City |

| Κυάνεαι | Kyaneae | Islands |

| Φαρνακεία | Pharnakeia | City |

| Σινώπη | Sinope | City |

| Χαλκηδών | Chalcedon | City |

| Καλύβη | Kalybe | City |

| Κανδαουία | Candabia | Mountain |

(Macedonia)

Concerning the ancient Macedonia Strabo says, “…indeed, Macedonia is a part of Greece. Following, however, the natural character of the country and its form, we have determined to separate it from Greece, and to unite it with Thrace, which borders upon it.”

Place names

| Μακεδονία/Ἠμαθία | Macedonia/Hemathia | Territory (previously Hemathia) |

| Ἐγνατία | Egnatia | Road |

| Κύψελλοι/Κύψελλα | Kypseloe/Kypsella | City |

| Ἕβρος | Ebros | River (Maritsa/Evros) |

| Λύχνιδος | Lychnidos | City |

| Pylon | Πυλών | City |

| Βαρνοῦς | Barnous | City |

| Ἡρακλεία | Heracleia | City |

| Ἔδεσσα | Edessa | City |

| Πέλλα | Pella | City |

| Θεσσαλονικεία/Θέρμη | Thessalonikeia/Therme | City |

| Στρυμών | Strymon | River |

| Θερμαίος | Thermaeos | Gulf |

| Νέστος | Nestos | River |

| Πάνορμος | Panormos | Port |

| Ὄγχησμος | Onchesmos | Port |

| Κασσιόπη | Cassiope | Port |

| Δωδώνη | Dodone | City |

| Αὐσόνιον | Ausonion | Sea |

| Φαλακρόν | Phalacron | Promontory |

| Ποσείδιον | Poseidion | City/Promontory |

| Βουθρωτὸν | Bouthroton | City |

| Πηλώδης | Pelodes | Port |

| Σύβοτα | Sybota | Islands |

| Λευκίμμα | Leucimma | Promontory |

| Χειμέριον | Chimerion | Promontory |

| Γλυκὺς | Glykys | Port |

| Ἀχέρων | Acheron | River |

| Ἀχερουσία | Acherusia | Lake |

| Θύαμις | Thyamis | River |

| Κίχυρος< Ἐφύρα | Cichyros< Ephyra | City |

| Φοινίκη | Phoenice | City |

| Βουχέτιον | Bouchetion | City |

| Ἐλάτρια | Elatria | City |

| Πανδοσία | Pandosia | City |

| Βατίαι | Batiae | City |

| Κόμαρος | Comaros | Harbor |

| Νικόπολις | Nicopolis | Harbor |

| Ἄρατθος | Arathos | River |

| Τύμφη | Tymphe | Mountain |

| Παρωραία | Paroraea | City |

| Ἄργος Ἀμφιλοχικόν | Argos Amphilochicon | City |

| Ἄργος Ὀρεστικόν | Argos Orestikon | City |

| Δαμαστίον | Damastion | City |

| Δευρίοπος | Deuriopos | City |

| Τρίπολις Πελαγονία | Tripolis Pelagonia | City |

| Ἤπειρος | Hepeiros | Territory |

| Ἐορδοὶ | Eordoe | City |

| Ἐλίμεια | Elimeia | City |

| Ἐράτυρα | Eratyra | City |

| Λύγκον | Lyngon | City |

| Ἀχελῶος< Θόας | Acheloos< Thoas | River |

| Εὔηνος/Λυκόρμας | Evenos/Lycormas | River (previously Lycormas) |

| Ἐρίγων/Ῥιγινία | Erigon/Riginia | River |

| Ἀξιὸς | Axios | River |

| Ἄζωρος | Azoros | City |

| Βρυάνιον | Bryanion | City |

| Ἀλαλκομεναὶ | Alalkomenae | City |

| Στύβαρα | Stybara | City |

| Αἰγίνιον | Aeginion | City |

| Εὔρωπος | Europos | City/river (Eurotas) |

| Κύδραι | Kydrae | City |

| Αἰθικία | Aethicia | City |

| Τρίκκη | Tricce | City |

| Ποῖον | Poeon | Mountain |

| Πίνδος | Pindos | Mountain (Pindus) |

| Ὀξύνεια | Oxyneia | City |

| Ἴων | Ion | River |

| Τομάρος/Τμάρος | Tomaros/Tmaros | Mountain |

| Mountain | Polyanon | Mountain |

| Γορτυνίον | Gortynion | City |

| Στόβων | Stobon | City |

| Ἁλιάκμων | Aliacmon | River |

| Θερμαῖος | Thermaeos | Gulf |

| Ὀρεστὶς | Orestis | Territory |

| Οἴτη | Oete | Mountain |

| Βοῖον | Boeon | Mountain |

| Βερτίσκος | Bertiscos | Mountain |

| Σκάρδος | Scardos | Mountain |

| Ὄρβηλος | Orbelos | Mountain |

| Ῥοδόπη | Rodope | Mountain |

| Αἵμος | Aemos | Mountain |

| Ἠμαθία | Hemathia | Mountain |

| Ὄλυμπος | Olympos | Mountain (Olympus) |

| Ὄλυνθος | Olynthos | City |

| Μαγνησία | Magnesia | Territory |

| Τιταρίον | Titarion | Mountain |

| Μαγνῆτις | Magnetis | City |

| Γυρτών | Gyrton | City |

| Κραννών | Crannon | City |

| Πιερία | Pieria | Gulf/Territory |

| Πήλιον | Pelion | Mountain |

| Δῖον | Dion | City |

| Πίμπλεια | Pimpleia | City |

| Λείβηθρα | Leibethra | City |

| Κίτρον/ Πύδνα | Citron /Pydna | City (previously Pydna) |

| Ἄλωρος | Aloros | City |

| Λουδίας | Ludias | River |

| Tρικλάρων | Triclaron | Mountain |

| Χαλάστρα | Chalastra | City |

| Ἀβυδών | Abydon | City |

| Αἶα | Aea | Spring |

| Ἐχέδωρος | Echedoros | City |

| Γαρησκὸς | Garescos | City |

| Αἴνεια | Aeneia | City |

| Κισσός | Kissos | City |

| Βέρμιον | Bermion | Mountain |

| Καναστραίον | Canastraeon | Promontory |

| Παλλήνη/Φλέγρα | Pallene/Phlegra | Peninsula (previously Phlegra) |

| Κασάνδρεια/Ποτίδαια | Casandreia/Potidaea | City (previously Potidaea) |

| Βέροια | Beroea | City |

| Ἄφυτις | Aphytis | City |

| Μένδη | Mende | City |

| Σκιώνη | Skione | City |

| Σάνη | Sane | City |

| Μηκύπερνα | Mekyperna | City |

| Τορωναίος | Toronaeos | Gulf |

| Δέρρις | Derris | Promontory |

| Ἄθως | Athos | Promontory/Mountain |

| Σιγγικὸς | Sigikos | Gulf |

| Σίγγος | Sigos | City |

| Ἄκανθος | Acanthos | City |

| Ἀκάνθιος | Acanthios | Gulf |

| Κωφός | Kofos | Port |

| Μαλιακὸς | Maliakos | Gulf |

| Παγασιτικὸς | Pagasitikos | Gulf |

| Στρυμονικὸς | Strymonikos | Gulf |

| Σηπιάς | Sepias | Promontory |

| Νυμφαῖον | Nymphaeon | Promontory |

| Ἀκράθως | Acrathos | Promontory |

| Νεάπολις | Neapolis | City |

| Κλεωναὶ | Kleonae | City |

| Θύσσος | Thyssos | City |

| Ὀλόφυξις | Olophyksis | City |

| Ἀκροθώοι | Akrothoe | City |

| Στάγειρα | Stageira | City |

| Κάπρος | Capros | Port/Island |

| Φάγρης | Phagres | City |

| Γαληψὸς | Galepsos | City |

| Ἀπολλωνία | Apollonia | City |

| Θρᾴκη/Θρῄκη | Thrace/Threce | Territory |

| Μύρκινος | Myrkinos | City |

| Ἄργιλος | Argilos | City |

| Δραβῆσκος | Drabiskos | City |

| Δάτον | Daton | City |

| Παγγαῖον | Pagaeon | Mountain |

| Οὐρανόπολις | Uranopolis | City |

| Αμφίπολις | Amphipolis | City |

| Ἐννέα ὁδοί | Ennea Odoe | City |

| Ἀγριάναι | Agrianae | City |

| Παρορβηλία | Parorbelia | City |

| Εἰδομένη | Eidomene | City |

| Καλλίπολις | Kallipolis | City |

| Ὀρθόπολις | Orthopolis | City |

| Φιλιππούπολις | Philippoupolis | City |

| Βέργη | Berge | City |

| Παιονία | Paeonia | City |

| Δόβηρον | Doberon | City |

| Βόλβη | Bolbe | City |

| Ἀρέθουσα | Arethusa | City |

| Μαίδων | Maedon | City |

| Σιντοὶ | Sintoe | City |

| Πέρινθος | Perinthos | City |

| Φίλιπποι/Κρηνίδες | Philippoe/Crenides | City (before Crenides) |

| Λῆμνος | Lemnos | Island |

| Θάσος | Thasos | Island |

| Ἴμβρος | Imbros | Island |

| Ἄβδηρα | Abdera | City |

| Δίκαια | Dikaea | City/port |

| Βιστονὶς | Bistonis | Lake |

| Καρτερὰ | Kartera | City |

| Ξάνθεια | Xantheia | City |

| Μαρώνεια | Maronia | City |

| Ἴσμαρος/Ἰσμάρα | Ismaros/Ismara | City |

| Ἰσμαρὶς | Ismaris | Lake |

| Θασίων κεφαλαί | Thasion cefalae | Rocks |

| Σαπαῖοι | Sapeoi | City |

| Τόπειρα | Topeira | City |

| Ὀρθαγόρεια | Orthagoreia | City |

| Τέμπυρα | Tempyra | City |

| Χαράκωμα | Characoma | City |

| Σαμοθρᾴκη< Παρθενία< Ἀνθεμίς< Μελάμφυλλος | Samothrace/Samos | Island |

| Παρθένιος> Ἴμβρασος | Parthenios> Imbrasos | River |

| Ἴμβρος | Imbros | Island |

| Ὀδρύσαι | Odrysae | City |

| Βιζύη | Bizye | City |

| Αἶνος | Aenos | City |

| Μέλας | Melas | Gulf/River |

| Σαρπηδών | Sarpedon | Promontory |

| Ἄβυδον | Abydon | Strait |

| Σηστόν | Seston | Strait |

| Λυσιμάχεια | Lysimaheia | City |

| Καρδία | Cardia | City |

| Πακτύη | Paktye | City |

| Δράβος | Drabos | City |

| Λίμναι | Limnae | City |

| Ἀλωπεκόννησος | Alopeconnesos | City |

| Μαζουσία | Mazusia | Promontory |

| Ἐλαιοῦς | Elaeus | City |

| Πρωτεσιλάειον | Protesilaeion | City |

| Σίγειον | Sigeion | Promontory |

| Τρῳάς | Troas | Territory |

| Κυνὸς/ Ἑκάβης σῆμα | Kynos/Hecabes sema | Promontory |

| Μάδυτος | Madytos | City |

| Σηστιὰς | Sestias | Promontory |

| Σηστός | Sestos | City |

| Κριθωτή | Krithote | City |

| Μακρὸν τεῖχος | Macron teichos | Territory |

| Λευκὴ ἀκτὴ | Leuce acte | Port |

| Ἱερὸν ὄρος | Ieron oros | Mountain |

| Σηλυβρία | Selymbria | City |

| Σίλτα | Silta | City |

| Προκόννησος | Proconnesos | Island (Marmara) |

| Ἀθύρας | Athyras | River |

| Βαθυνία | Bathynia | River |

| Βυζάντιον | Byzantion | City |

| Κυανέαι πέτραι | Cyaneae petrae | Islands/Reefs |

| Σιγείος | Sigeios | City |

| Λάμψακος | Lampsacos | City |

| Κύζικος | Kyzicos | City |

| Πάριος | Parios | City |

| Πρίαπος | Priapos | City |

| Σιγρίον | Sigrion | Promontory |

| Τροία | Troea | City |

| Ἕλλα | Ella | Strait |

2.8 Greece

(Without Macedonia)

About the origin of the Greek language Strabo says,

“Hecatæus of Miletus says of the Peloponnesus, that, before the time of the Greeks, it was inhabited by barbarians. Perhaps even the whole of Greece was, anciently, a settlement of barbarians, if we judge from former accounts. For Pelops brought colonists from Phrygia into the Peloponnesus, which took his name; Danaus brought colonists from Egypt; Dryopes, Caucones, Pelasgi, Leleges, and other barbarous nations, partitioned among themselves the country on this side of the isthmus. The case was the same on the other side of the isthmus; for Thracians, under their leader Eumolpus, took possession of Attica; Tereus of Daulis in Phocæa; the Phœnicians, with their leader Cadmus, occupied the Cadmeian district; Aones, and Temmices, and Hyantes, Bœotia. Pindar says, 'there was a time when the Bœotian people were called Syes.' Some names show their barbarous origin, as Cecrops, Codrus, Œclus, Cothus, Drymas, and Crinacus. Thracians, Illyrians, and Epirotæ are settled even at present on the sides of Greece. Formerly the territory they possessed was more extensive, although even now the barbarians possess a large part of the country, which, without dispute, is Greece. Macedonia is occupied by Thracians, as well as some parts of Thessaly; the country above Acarnania and Ætolia, by Thesproti, Cassopæi, Amphilochi, Molotti, and Athamanes, Epirotic tribes…”

“Bœotia was first occupied by Barbarians, Aones, and Temmices, a wandering people from Sunium, by Leleges, and Hyantes. Then the Phœnicians, who accompanied Cadmus, possessed it… (The Aeolians) after having united the Orchomenian tract to Bœotia (for formerly they did not form one community, nor has Homer enumerated these people with the Bœotians, but by themselves, calling them Minyæ) with the assistance of the Orchomenians they drove out the Pelasgi, who went to Athens, a part of which city is called from this people Pelasgic. The Pelasgi however settled below Hymettus. The Thracians retreated to Parnassus. The Hyantes founded Hyampolis in Phocis…

Ephorus relates that the Thracians, after making treaty with the Bœotians, attacked them by night, when encamped in a careless manner during a time of peace… The Pelasgi and the Bœotians also went during the war to consult the oracle (at Dodona). The messengers (of the Bœotians) sent to consult the oracle suspecting the prophetess of favoring the Pelasgi on account of their relationship, (for the temple had originally belonged to the Pelasgi,) seized the woman, and threw her upon a burning pile…

After this they assisted Penthilus in sending out the Æolian colony, and dispatched a large body of their own people with him, so that it was called the Bœotian colony…”

“The poet next mentions the Orchomenians in the Catalogue, and distinguishes them from the Bœotian nation. He gives to Orchomenus the epithet Minyeian from the nation of the Minyæ. They say that a colony of the Minyeians went hence to Iolcus, and from this circumstance the Argonauts were called Minyæ. It appears that, anciently, it was a rich and very powerful city… Of its power there is this proof, that the Thebans always paid tribute to the Orchomenians, and to Erginus their king, who it is said was put to death by Hercules... The spot which the present lake Copaïs occupies, was formerly, it is said, dry ground, and was cultivated in various ways by the Orchomenians, who lived near it; and this is alleged as a proof of wealth…”

“The island (Euboea) had the name… of Abantis also. The poet (Homer) in speaking of Eubœa never calls the inhabitants from the name of the island, Eubœans, but always Abantes. Aristotle says that Thracians, taking their departure from Aba, the Phocian city, settled with the other inhabitants in the island, and gave the name of Abantes to those who already occupied it; other writers say that they had their name from a hero, as that of Eubœa was derived from a heroine. But perhaps as a certain cave on the sea-coast fronting the Ægean Sea is called Boos-Aule, (or the Cow’s Stall) where Io is said to have brought forth Epaphus, so the island may have had the name Eubœa on this account…”

“Some writers identify (Cephallenia) with Taphos, and the Cephallenians with Taphians, and these again with Teleboæ. They assert that Amphitryon, with the aid of Cephalus, the son of Deioneus, an exile from Athens, undertook an expedition against the island, and having got possession of it, delivered it up to Cephalus… But this is not in accordance with Homer, for the Cephallenians were subject to Ulysses and Lærtes, and Taphos to Mentes. Nor does Hellanicus follow Homer when he calls Cephallenia, Dulichium, for Dulichium, and the other Echinades, are said to be under the command of Meges, and the inhabitants, Epeii, who came from Elis…”

As far as the Taphians (Leleges) of Cephalonia are concerned, according to Wikipedia they were one of the aboriginal peoples of the Aegean littoral, distinct from the Pelasgians, the Bronze Age Greeks, the Cretan Minoans, the Cycladic Telkhines, and the Tyrrhenians. The classical Hellenes emerged as an amalgam of these six peoples. The distinction between the Leleges and the Carians (a nation living in south west Anatolia) is unclear. According to Homer, the Leleges were a distinct Anatolian tribe; However, Herodotus states that Leleges had been an early name for the Carians. The fourth-century BCE historian Philippus of Theangela, suggested that the Leleges maintained connections to Messenia, Laconia, Locris and other regions in mainland Greece, after they were overcome by the Carians in Asia Minor.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leleges]

It is uncertain if the Leleges were the ancestors of the Carians or if they were displaced by the later in Asia Minor in the beginning and in mainland Greece later on. Another interesting example is the Caucones:

“The Triphylii had their name from the accident of the union of three tribes; of the Epeii, the original inhabitants; of the Minyæ, who afterwards settled there; and last of all of the Eleii, who made themselves masters of the country…

At present I must add some remarks concerning the Caucones in Triphylia. For some writers say, that the whole of the present Elis, from Messenia to Dyme, was called Cauconia. Antimachus calls them all Epeii and Caucones. But some writers say that they did not possess the whole country, but inhabited it when they were divided into two bodies, one of which settled in Triphylia towards Messenia, the other in the Buprasian district towards Dyme, and in the Hollow Elis. And there, and not in any other place, Aristotle considered them to be situated. The last opinion agrees better with the language of Homer, and the preceding question is resolved. For Nestor is supposed to have lived at the Triphyliac Pylus, the parts of which towards the south and the east (and these coincide towards Messenia and Laconia) was the country subject to Nestor, but the Caucones now occupy it, so that those who are going from Pylus to Lacedæmon must necessarily take the road through the Caucones.”

For the Caucones Wikipedia says they were an autochthonous tribe of Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) whose migrations brought them to the western Greek mainland in Arkadia, Triphylian Pylos, and north into Elis. Their etymology suggests strong affinities with the Caucasos Mountains originally. According to Herodotus and other classical writers, they were displaced or absorbed by the immigrant Bithynians, who were a group of clans from Thrace that spoke an Indo-European language. Thracian Bithynians also expelled or subdued the Mysians, and some minor tribes, the Mariandyni alone maintaining themselves in cultural independence, in the northeast of what became Bithynia. Strabo acknowledges that in earlier times Bithynians were called Mysians who, in turn, Herodotus says alongside Teucrians were invaders of northern Greece (Thessaly) before the Trojan War.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caucones]

Strabo’s story about the three tribes of Triphylia (= treis phyles, three tribes), the Epii, Minyans and Eleii doesn’t clarify the linguistic affinities between them. If the Epii were the original inhabitants then probably they were Pelasgi. Minyans could be either Minoans (from Minos) or Thracians (from Minyas). The Eleii if they were the last to arrive in Triphylia could be Greeks but their relation to the Caucones is uncertain.